Governor Jerry Brown 2.0: Judicial Appointments, Now New And Improved

In this article we evaluate two points held by today’s conventional wisdom. One posits that Jerry Brown has, in his second stint as governor, been slow to fill judicial vacancies, and that there is an unusually high number of open judicial seats. The other is a suspicion that the judicial appointments by Governor Brown version 2.0 will be in the style of Governor Brown version 1.0. Our evaluation is that both theories are empirically less than true.

(Recognizing that the first Governor Brown was Jerry Brown’s father Pat Brown, for convenience we will ignore that fact.)

To the first point about vacancies, the available data does support several conclusions. The number of empty Superior Court seats in California began to increase significantly, coinciding with the beginning of the second Brown administration in January 2011. Presently, the average number of Superior Court vacancies since January 2011 is 63.5—compared with seven such vacancies in January 2011, the month the second Brown administration began. After an initial spike, the number of Superior Court vacancies has remained consistent over the course of Brown’s administration.

But the available data does not strongly support the conclusion that the average number of vacancies is unusually high. Nor does it conclusively establish that the present Brown administration is slower or faster than other governors in filling vacancies.

To the second point about appointee characteristics, there is no question that the justices appointed to the California Supreme Court during the first Brown administration were novel and in some cases controversial. Although one element of the Brown appointment process—finding novel appointees—remains visible today, the element of controversy surrounding the modern appointees is absent. Instead, the most salient aspect of the current crop of Brown 2.0 appointees to the state high court is their sterling qualifications. That’s not exactly a negative.

In summary: Governor Brown 2.0 is still a maverick, but he’s older and wiser.

Is there a comparatively high number of judicial vacancies? And is Governor Brown slow to fill them?

In 2014 the California Supreme Court lost two justices to retirement: Kennard and Baxter. The best evidence supporting the charge that Governor Brown has been slow to fill judicial vacancies is the lengthy delay in filling Justice Kennard’s seat. After Justice Kennard’s retirement on April 5, 2014, the court spent seven months with an empty chair until the governor nominated now-Justice Kruger to fill it. (Technically, the delay was closer to nine months, as Justice Kennard announced her retirement two months earlier.)

Contrast the inaction—or at least slow action—on filling Justice Kennard’s seat with the response to Justice Baxter’s announcement in June 2014 that he would not stand for retention. Governor Brown nominated now-Justice Cuéllar just five weeks later. This ensured that the court never had two openings, as Justice Cuéllar was approved by the voters in the November 4, 2014 election and assumed Justice Baxter’s seat in January immediately upon it becoming vacant.

At best, then, one can fairly say that Governor Brown waited an unusually long time—perhaps a delay of unprecedented length—before filling a vacancy on the state high court. But that is one delay, in filling one seat, on one court. That alone does not demonstrate a pattern. We must employ a broader perspective.

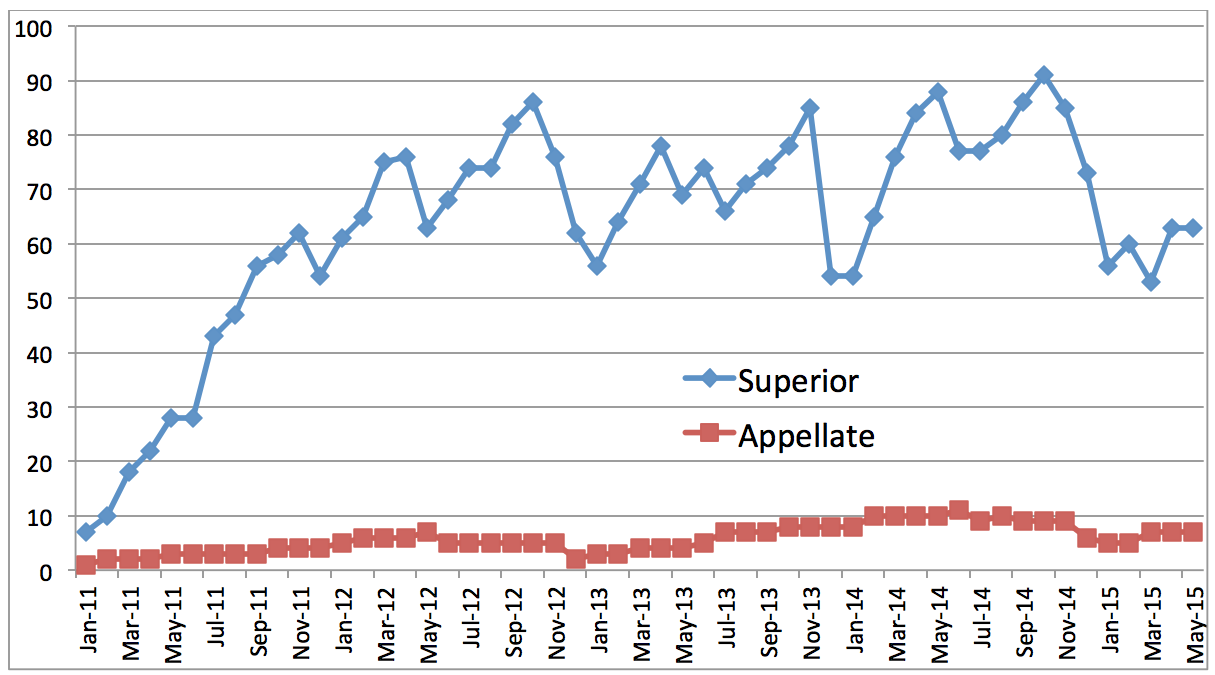

The more important consideration is not the rate at which Governor Brown fills seats, but the consistency of the total number of vacancies. A low number of vacancies with a low fill rate can be expected to have a lesser impact on judicial efficiency than a high number of vacancies coupled with a low fill rate; in the second scenario, more seats stay empty for a longer period. Consider Table 1 below, which shows vacant seats in all California courts per month.

Table 1 Source: California Judicial Council Judicial Vacancy Reports

This data does support the conclusion that a number of judicial seats in California are now empty, and that an increase in the number of empty Superior Court seats coincides with the beginning of the second Brown administration in January 2011. But this data is inadequate to prove the hypothesis that the present average number of vacancies is unusually high. The California Judicial Council only began tracking judicial vacancies in 2011, so it is impossible on these numbers to say anything about the historical average vacancy rate. And we know nothing about why vacancies spiked; it could be from buildup due to a slow appointments process, or something else entirely.

Nor is there clear support for a conclusion that the present Brown administration is slower or faster than other governors in filling vacancies. This is partly due to the difficulty of compiling a per-governor judicial appointments list. The list of Brown 2.0 judicial appointees is readily available. His office has been quoted as saying that he has appointed more than 200 judges in his second turn in the governor’s office. According to one compilation, the total presently stands at 245.

Data is scarce on judicial seats left vacant by other governors. One publication put the total number of judicial appointments by Governor Schwarzenegger at 627. Those appointment numbers (245 Browns in about four years, 627 Schwarzeneggers in eight years) suggest that Governor Brown is not on pace to equal the number of appointments by his immediate predecessor in office. This contradicts the theory, sometimes advanced, that Governor Brown is in a position to dramatically shift the composition of California courts. But it does provide some support for the claim that Governor Brown is not acting quickly to fill vacant judicial positions, at least compared with the previous administration.

The total appointment numbers are of limited value, as they say nothing about how quickly an administration filled seats, or how many were open at any given time. Simply comparing total appointments also ignores variables such as the number of authorized judicial positions (which generally has grown slowly over time) and the number of vacancies that occurred during a governor’s term. For example, the 1994 Overview of the Courts shows a total of 1,544 judicial officers, while the 2014 Court Statistics Report shows over 2,136 total judicial officers. Thus, while the Brown/Schwarzenegger total appointment numbers comparison has some value regarding the pace of appointments, it is not conclusive.

These problems with comparing the rate of filling vacancies also apply to the overall number of vacant seats at any given time. The numbers show that Governor Brown has permitted a number of seats to become vacant through natural attrition, and has left them vacant. Is an average number of 63.5 Superior Court vacancies since January 2011 a relatively high number? California has the nation’s largest judicial system, with more than twice as many judges as the entire federal judiciary. Out of the 2,136 statewide judicial positions presently authorized, 63.5 vacant positions is a vacancy rate of approximately 3 percent. By contrast, the current vacancy rate in the federal system is nearly 7 percent (59 vacancies out of 880 Art. III & I seats). Proportionally, that is a much higher vacancy figure.

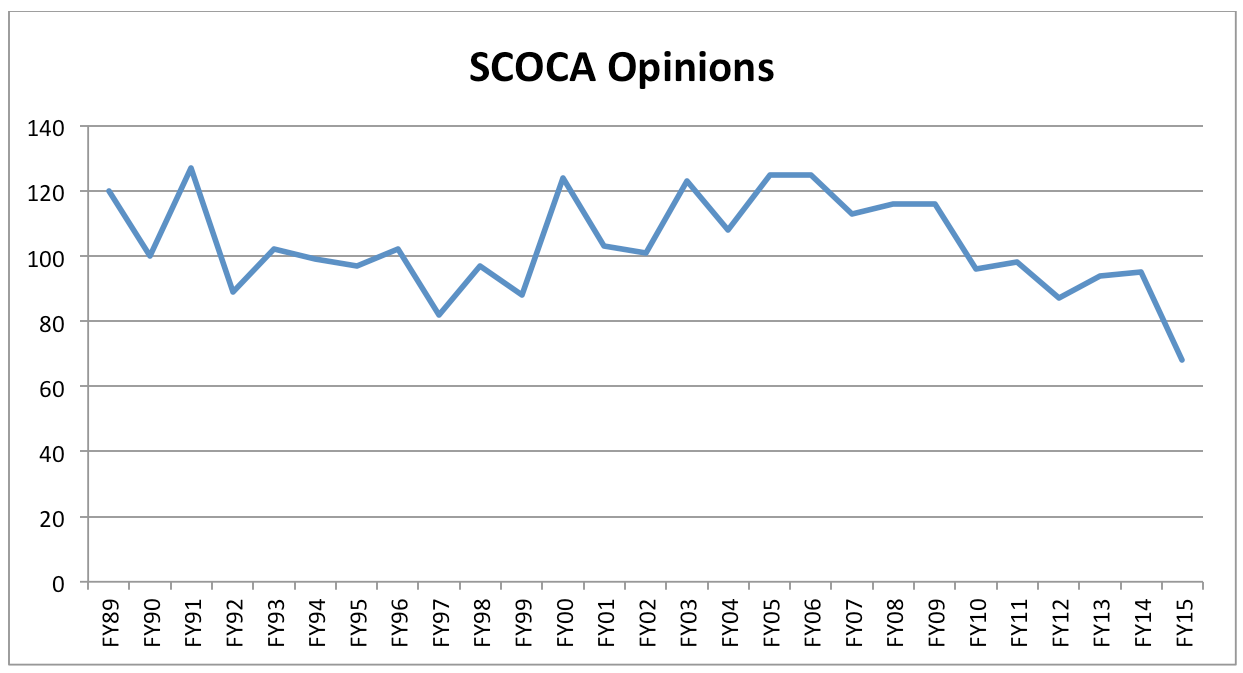

A related issue is the impact of vacancies on the workflow performance of the courts, in the sense of their ability to efficiently handle their caseloads. One commonly-used metric is the productivity of the state high court, measured in the number of opinions it issues. This is somewhat like judging the health of the U.S. economy by examining a stock price index: an uncertain barometer at best. But it is useful here to provide an output performance metric for the state’s most visible court. Consider Table 2 below, which shows the number of California Supreme Court opinions per year.

Table 2 Source: Court Statistics Reports

The average number of California Supreme Court opinions per fiscal year over this 27-year period is 99.82. Note that the data for fiscal 2014 and 2015 was compiled from public records, while the other years are totals from the Judicial Council annual reports. (In addition, six weeks remain in fiscal year 2015, and any opinions that may issue in that period naturally are not reflected in the data.) There is a negative trend in the number of opinions per year, beginning in the period following 2007. It is fair to suspect that the unusually significant decrease in the court’s productivity thus far in 2015 (68 opinions so far, about 32% below the average) is related to the retirements of justices Kennard and Baxter. Thus, at least for the California Supreme Court, vacancies and delay did seem to have an adverse effect on that court’s productivity.

Of course, that is only one court, and a small one. What effects, if any, are observable in the trial courts? There the data is much less clear.

The 2014 Court Statistics Report states that although the number of authorized trial court positions for the year was 2,024, the assessed number of judges needed was 2,286. Adding the average of 64 open seats, the trial courts were understaffed by 326 judges, or 14 percent. The trend does show that the dispositions rate is decreasing—but so is the rate of new filings. In fact, the figures for filings and dispositions (overall and per judge) show proportionally the same downward trend for the past several years. If the reduction in judges (and resulting increase in per-judge caseload) were affecting productivity as measured by dispositions, then the dispositions rate should be falling more rapidly than the filings. Similarly, the civil caseload clearance rates are trending down, but not greatly so, and the same is true for civil case processing time. On the criminal side of the docket, the rate of processing cases on time targets is mixed; by some measures criminal cases are being processed more efficiently. A staffing shortfall of 14 percent is not insignificant, but on these numbers it has not produced an equivalent significant effect on trial court output.

We suspect that the distinction between the observable effect of staffing on productivity of the California high court and the trial courts is due to their relative sizes. Losing one or two out of seven members is a 14 or 29 percent reduction, while leaving 64 out of 2,024 trial court positions open is a vacancy rate of just 3 percent. Thus, it is not surprising that the change in productivity differs significantly. This shows why it is misleading to use the state high court as an example of any failure or delay in filling vacancies, or the supposed effect on the courts’ workload: it simply is not representative of the courts as a whole.

On this evidence, one cannot draw any broad comparative conclusions about the average number of vacancies, nor about this administration’s rate of filling vacancies for the California judiciary generally. At most we can conclude that the number of vacancies has remained at its present level consistently for approximately the past four years. As for why that is so, there are two plausible contributing factors here.

The first is a well-known and acknowledged Brown characteristic: he’s a frugal man. Governor Brown said as much to the Christian Science Monitor (February 17, 2011) in defending himself against attacks on his fiscal conservatism by insisting, “It’s not because I’m conservative. It’s because I’m cheap.” See also Phil Matier, KCBS October 20, 2014 (“Another reason why Gov. Brown isn’t spending is simply because he’s notoriously cheap”), Los Angeles Times, August 4, 2010 (“For Jerry Brown, it seems no expense is too small to scrimp on”).

The second is perhaps a variation on the first. Consistent with his “do more with less” paradigm, Governor Brown may think that the state has more judgeships than it needs, and so he questions the need to fill vacant judgeships. Justice J. Anthony Kline, a Brown confidant, was quoted to that effect in the San Francisco Chronicle (November 29, 2014): “He wasn’t persuaded that the judicial branch was operating as efficiently as it could.” Noted SCOCA scholar Professor Gerald Uelmen concurred: “He’s always taken the position that the courts are overstocked.” Indeed, in his first administration Governor Brown as accused of being slow to appoint judges. Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen , Justice Stanley Mosk: A Life at the Center of California Politics and Justice (McFarland 2012) at 181.

And one cannot neglect the effect of the tripartite nature of the state government and the budget process. The legislature determines the number of Superior Court judges statewide, authorizing a number in county-by-county statutes, beginning with Alameda in Government Code section 69580. The legislature similarly authorizes the number of justices in the Court of Appeal by statute, beginning with Government Code section 69100. The membership of the California Supreme Court is set at seven by Article 6 section 2 of the state constitution. And of course, the governor and the legislature must agree on a budget that actually funds any existing or newly created positions. The legislature may not agree to additional court funds, or the governor may line-item veto them, or the legislature may not appropriate funds. Thus, even if the legislature approves new judgeships, they may not be funded—as has been the case in recent years.

Are the Governor Brown 2.0 appointments comparable to those of Governor Brown 1.0?

Turning to the second issue regarding the nature of the Brown 2.0 appointments, a criticism of his first turn (and a concern sometimes voiced about his second) is that the judiciary will be thrown into turmoil by appointments that are so out of step as to be politically unviable. In other words, will we see another Rose Bird event?

We start with an overview of the first set of appointments.

Wiley Manuel (Hastings) was the first African American justice. Rose Bird (Berkeley) was the first woman, and the first female Chief Justice. Frank Newman (Berkeley) was a professor at Berkeley Law—though not the first distinguished academic from that institution appointed to the court, nor the last. Otto Kaus (Loyola) was perhaps the most conventional appointment, having served on the Superior Court and the Court of Appeal. Allen Broussard (Berkeley), the second African American justice on the court, had been a Municipal and a Superior Court judge. Cruz Reynoso (Berkeley) was the first Hispanic justice on the court. And Joseph Grodin (Yale) was a professor at Hastings when Governor Brown appointed him to the Court of Appeal, three years before elevating him to the state high court.

Justices Broussard, Kaus, and Reynoso were the subjects of an opposition campaign during their retention elections in 1982; all were retained, but with relatively low majorities. A much stronger opposition campaign was waged against Chief Justice Bird and Justices Grodin and Reynoso in the November 1986 election, which resulted in their removal from the court. The history of the Bird court and its fall is lengthy, complex, and polarizing. One view that seems to be widely held in the years following is that the appointees of Governor Jerry Brown 1.0 were too radically liberal.

Given that history, one could wonder whether Governor Jerry Brown 2.0 would make the same sort of appointments in his second turn. If his appointments to the California Supreme Court are representative, they do not support that conclusion. Although they all exhibit characteristics that mark them with the unique Jerry Brown stamp, there is a striking contrast between SCOCA appointments set 1 (Bird, Grodin, Reynoso) and set 2 (Liu, Cuéllar, Kruger).

One similarity can be expressed with an unfortunate colloquial phrase that sometimes is heard in the process of vetting judicial candidates in California: judicial bling. A shiny candidate has a sparkly resume, studded with bright jewels like a SCOTUS clerkship, or the precious gem of a tenured professorship at a prestigious school, or is gilded with the polished gleam of a double Yale or a triple Harvard set of degrees. The kind of solid-platinum qualifications that any rational person naturally would think augur good future performance on the bench. So while the moniker is irreverent, the concept is at the core of the process of vetting judicial candidates.

Regardless of whether Governor Brown’s judicial appointments team thinks of the process in this manner, there is no question that his recent appointments to the California Supreme Court have glittering qualifications. This is not to say that the first set of appointments were unqualified (quite the opposite), only that it is difficult to not be impressed by the resumes of set two.

Justice Liu: Stanford B.A., Oxford M.Phil., Yale J.D. SCOTUS and D.C. Circuit clerk. Professor at Berkeley Law.

Justice Cuéllar: Harvard B.A., Yale J.D., Stanford Ph.D. Ninth Circuit clerk. Professor at Stanford Law.

Justice Kruger: Harvard B.A., Yale J.D. SCOTUS clerk. Second in command at the U.S. Solicitor General’s Office, with numerous SCOTUS arguments.

Shiny appointments indeed.

The other similarities between the two sets of appointees are youth and the lack of prior judicial experience. For example, Professor Gerald Uelmen pointed out that Justice Kruger is one of the youngest justices in the court’s history (she’s 38), and barely meets the constitutional qualification of being admitted to practice in California for 10 years. The same can be said for perhaps the greatest California Supreme Court justice: When appointed to the court Roger Traynor was a 40-year-old law professor at Berkeley who had only been a lawyer for 13 years. (Some publications have called Justice Kruger the court’s “youngest” member ever. This is incorrect. Justice Murray joined at 26, the infamous Justice David Terry and Justices Wells and Bryan were 32, Justice Bennett was 34, Chief Justice Hastings and Justice Cope were 35, Justice Heydenfeldt was 36, and Justice Paterson was 37.)

The big difference between the two sets is the absence of drama. So far there is little support for the view that a tsunami is heading toward the Brown 2.0 appointees. Justice Liu and Justice Cuéllar both stood for retention in the November 2014 general election, and both were confirmed by substantial majorities to the 12-year terms authorized by the California Constitution. Any campaign against them would have to wait until 2026. And although it is possible that a justice could be subjected to a recall campaign, that is hardly a concern at this point. Justices Liu and Cuéllar were retained by two-thirds margins last fall. Justice Kruger took her seat on January 5, 2015—after Justice Kennard’s term expired. Because Justice Kruger was a vacancy appointment, she will stand for retention at the next general election (November 2016), giving her plenty of time to establish a solid judicial record. (See Cal. Const., art. 6, § 16 (d)(2).) Thus, unless circumstances change dramatically, it seems unlikely that another coalition will build around unseating the present Brown 2.0 appointees.

Conclusion

This data provides some support for the conclusion that the rate of filling judicial vacancies by Governor Brown is below the historical average, at least compared to Governor Schwarzenegger. But it does not strongly support such criticism. This data also provides some support for the conclusion that a consistent number of judicial vacancies exists at any given time. But it is not a high number: on average in the past four years, approximately three percent of the state’s judicial positions are open at any given time. Leaving judicial seats unfilled can create hardships for the courts and impede the public’s access to justice, and one expects this to become more true the more seats are open and the longer they stay empty. This was true regarding the open positions on the state high court in the past year, which coincide with an approximately one-third drop in that court’s productivity. No doubt Governor Brown would respond that open seats on the bench save the state money, and the courts are encouraged to do more with less. And the data for the trial courts does not show their workload and productivity numbers diverging—if anything, overall civil filings are down, and the disposition rates have declined proportionally.

We can look forward to another 200 to 300 Brown appointments (possibly even one or two more SCOCA appointments) to the California bench in the next few years. And the characteristic Jerry Brown style of appointing surprisingly exceptional candidates remains visible, perhaps even more so than in his first administration. But presently there is little prospect of those appointees causing another upheaval in the courts.

Senior Research Fellow Stephen M. Duvernay contributed to this article.

- BREAKING: Law bloggers mostly agree with each other - January 20, 2026

- About counting cases - January 7, 2026

- SCOCA year in review 2025 - January 4, 2026