Petitions for Review: A Long-Odds Gambit

Here we review and analyze the grant rate data for SCOCA review petitions. Our conclusion is that, on average, any given petition has a 4% chance of being granted.

The Court’s Role in the California Judiciary

We begin with context. The Supreme Court of California is the state’s highest court, and its primary role is to resolve the big questions, settle appellate court splits, and ensure uniformity in the law. California Rules of Court, Rule 8.500(b)(1). Granted, capital cases (discussed below) are an exception to this, but the fact remains that in the majority of the cases SCOCA hears, the court does not function as a forum for final review of appellate court errors. Instead, the state high court chooses the issues it deems sufficiently important to warrant its attention. This has important consequences for appellate practitioners.

The Jurisdiction Provisions of the State Constitution Give the Court Near-Complete Control Over Its Docket

Again, context is important here. The distinction between the court’s original and appellate jurisdiction is practically unimportant because, except for capital cases, the court’s jurisdiction is entirely discretionary. As a result, generally the court has complete discretion to grant review in only those cases it considers sufficiently important to warrant its attention.

Several provisions in Article 6 of the state constitution define state court jurisdiction.

Article 6, section 10 defines original jurisdiction: “The Supreme Court, courts of appeal, superior courts, and their judges have original jurisdiction in habeas corpus proceedings. Those courts also have original jurisdiction in proceedings for extraordinary relief in the nature of mandamus, certiorari, and prohibition. …”

Article 6, section 11(a) defines appellate jurisdiction: “The Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction when judgment of death has been pronounced. With that exception courts of appeal have appellate jurisdiction … .”

Article 6, section 12 permits transfer of cases:

- “(a) The Supreme Court may, before decision, transfer to itself a cause in a court of appeal. It may, before decision, transfer a cause from itself to a court of appeal or from one court of appeal or division to another. The court to which a cause is transferred has jurisdiction.” (emphasis added).

- “(b) The Supreme Court may review the decision of a court of appeal in any …” (emphasis added).

- “(d) This section shall not apply to an appeal involving a judgment of death.”

In summary, the court can hear or transfer any non-capital appeal. The court alone is responsible for reviewing capital cases.

All California courts have original jurisdiction to hear petitions for habeas corpus, mandamus, certiorari, and prohibition. The high court’s original jurisdiction, coupled with its power to transfer cases, results in this practical reality: while a practitioner may file a petition for extraordinary relief initially and directly in the state’s highest court, the matter will be transferred to a lower court except in the most unusual circumstances. (Note that this excludes the two to three thousand noncapital habeas petitions the court receives—and acts on without transferring—each year.)

Together, these provisions give this result: the court’s only mandatory jurisdiction is the trial court judgments of death, in which cases it functions as an appellate court. In all other cases the court’s jurisdiction is permissive.

The conventional wisdom holds that the court’s criminal docket, and the capital appeals in particular, have overwhelmed the court and resulted in other matters receiving less than their deserved amount of the court’s attention. We conclude that this is not true.

Overall Incoming and Outgoing Case Data

All of the data herein is taken from the Judicial Council of California’s annual Court Statistics Reports, available at http://www.courts.ca.gov/13421.htm

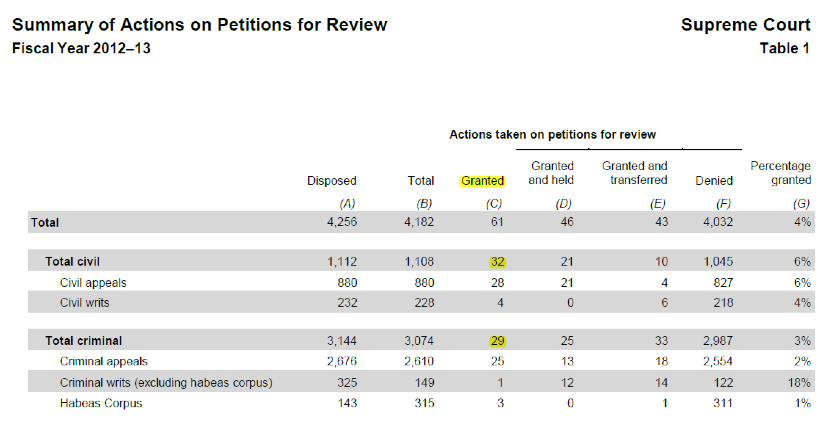

Consider the data from this recent sample year, fiscal 2012-13.

- The court issued 94 written opinions during the year.

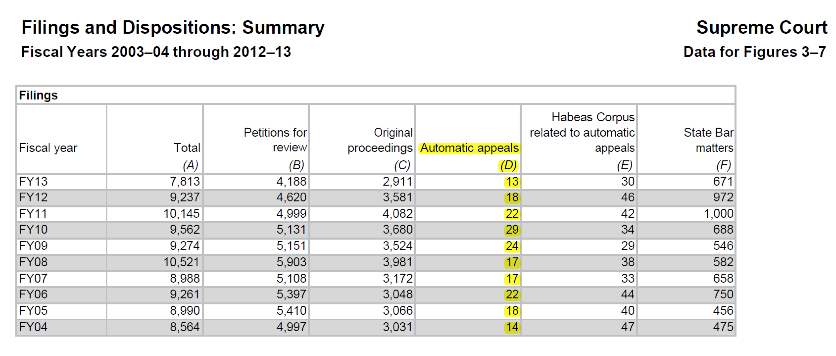

- The court received 4,188 petitions seeking review from a Court of Appeal decision in an appeal or an original writ proceeding.

- 1,108 of these petitions for review arose from civil matters, and 3,080 from criminal matters.

- The court received 2,911 petitions seeking original writ relief.

- Of the petitions seeking original writ relief, 174 arose out of civil matters and 2,737 arose out of criminal matters.

- A total of 13 automatic appeals were filed following a judgment of death, and the court disposed of 21 capital appeals by opinion.

- The court received 30 habeas petitions related to automatic appeals.

There are several important takeaways from these numbers. First, we can conclude that the automatic appeals do not significantly contribute to the volume. Compare the 13 automatic appeals to the 4,188 review petitions; the ratio 13:4,188 is vanishingly small, and the automatic appeals represent only 0.3% of the petitions for review. The comparison is even more dramatic if the 2,911 original jurisdiction matters are included: 13:7,099, or just 0.1%.

Second, we can conclude that the automatic appeals are not disproportionately represented in the cases that make it onto the court’s docket. Instead, the court’s docket is divided roughly into thirds between capital appeals, civil cases, and non-capital criminal cases.

(Click to expand)

Similarly, the annual volume of capital opinions is approximately equivalent to the number of decisions issued in civil cases and non-capital criminal cases. The court issued 94 opinions in the sample year, 21 of which were capital appeals or 22% of the total number of opinions. This is consistent with the figure former Chief Justice Ronald M. George sometimes employed: in his view, capital cases (combining appeals and habeas) take about 25% of the court’s time and attention.

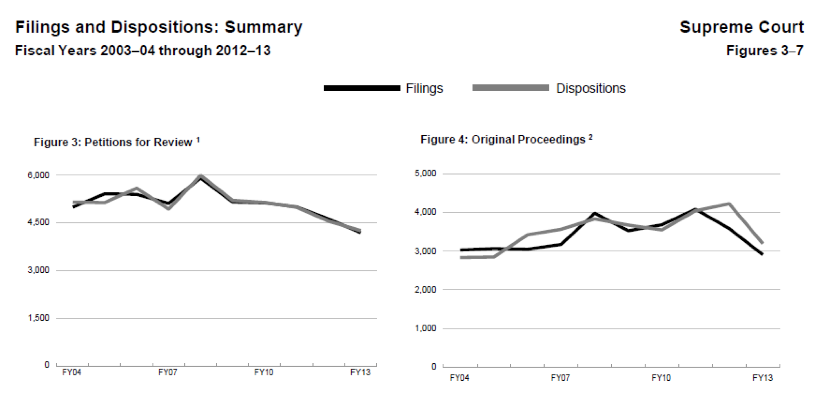

Finally, for the past 10 years, the ratio of incoming to outgoing capital cases has been close to 1:1, which means that the court is not building a backlog of capital cases. One can also see that while the number of filings (original and petitions) is declining, the dispositions rate for both case types declines at very nearly the same rate. Thus, a reduction in the number of requests for the court’s attention does not correspond with any increase in the court’s capacity to accept cases. And as explained in “Governor Jerry Brown 2.0: Judicial Appointments, Now New and Improved,” the average number of opinions declined for the past 10 years, so there similarly is no correlation between a decline in filings and an increase in the court’s capacity to issue decisions. Instead, the opposite is true: filings and dispositions both declined over the past 10 years.

(Click to expand)

It is true that 74% of the review petitions were in criminal cases; similarly, 94% of the original petitions were in criminal cases. But that disparity is not represented in the number of civil and non-capital criminal cases accepted for review. Instead, those cases are accepted for review in approximately equal numbers to one another and to capital appeals. Thus, the higher number of criminal requests for the court’s attention is irrelevant to this analysis, as it shows nothing about how criminal cases (capital and non-capital) affect the court’s docket. At most it is relevant to the time spent in reviewing petitions, but the data is silent on that issue and so we do not consider it here.

The historical data is consistent with the sample year discussed above. For the most recent 10-year period, the court received an average of 19.4 capital appeals each year.

(Click to expand)

(Click to expand)

The Grant Rate

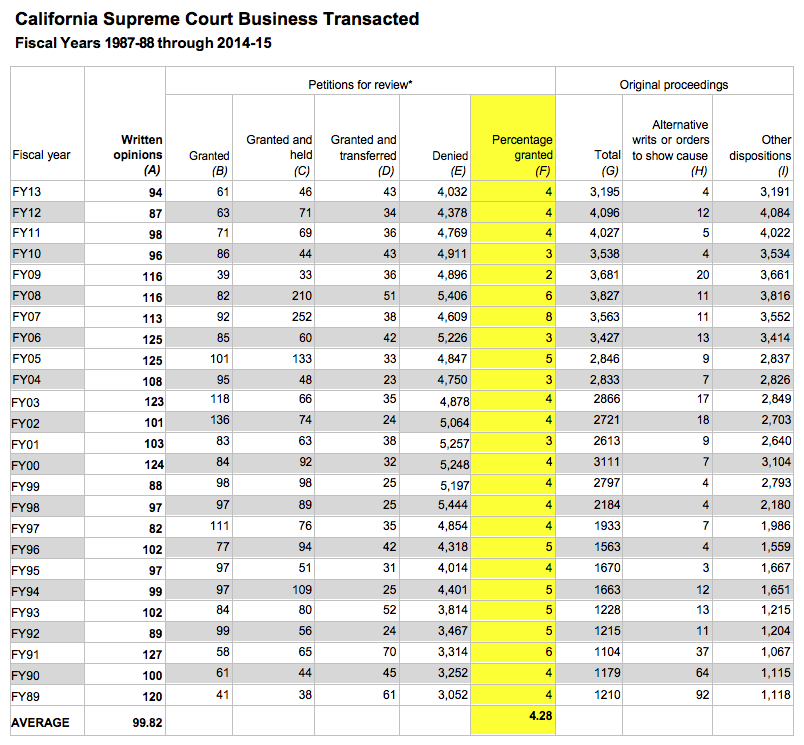

For the sample year, the overall grant rate was 4%. The civil grant rate was 6%, and the criminal grant rate was 3%.

(Click to expand)

The grant rate in the sample year is consistent with the 25-year average grant rate, which was 4.28%.

(Click to expand)

In summary, the odds of getting any given civil petition granted are around 4%. The odds of getting any given non-capital criminal petition granted are about 3%. On these numbers, any petition is exceedingly unlikely to be granted. (Note that recently the court has been granting and holding more frequently than in the past. Thus, the grant statistics may appear to spike going forward from the sample year, and grants will look artificially high without controlling for grant and holds.)

Conclusion

Does this data mean that non-capital review petitions are less likely to be granted because of the capital caseload? Not necessarily. True, theoretically the court could grant more review petitions if it had no capital cases. But the court must always consider whether any given petition merits its time and attention. And removing the capital cases would only open around 20 slots per year. So even without the capital docket, a petition for review still would be a low percentage gambit.

More importantly, the overall grant rate has remained largely unchanged over the most recent 25-year period. This means that the grant rate shows no substantial change due to fluctuations in (1) the number of capital appeals, (2) the composition of the court in a given year, (3) the declining number of petitions being filed, or (4) any decline in the number of opinions. Thus, while the inflow and outflow generally remains at a 1:1 ratio (i.e., the court is disposing of cases at nearly the same pace as they arrive), on average in any given case in any given year, the likelihood of any petition for review being granted is approximately 4%.

It seems that none of the factors in this dataset are responsible for this surprisingly consistent grant rate. The factor that ultimately determines the court’s decision rate is time. The number of justices—seven—is set by Article 6, section 2 of the state constitution. Those seven justices may have only 200 or so working days a year; given that the court in recent years has issued around 100 written opinions per year, this means that the court issues an opinion almost every other working day, on average. Roy A. Gustafson, Some Observations about California Courts of Appeal (1971) 19 UCLA L. Rev. 167, 177. As we described in “SCOCA Chambers Staff: Annual Clerks or Staff Attorneys – or Both?,” the justices are substantially aided in their work by the judicial staff attorneys. Indeed, as explained there, it is unlikely that the court could function without them. Barring some significant change in either the number of justices, or the staff budget, this data suggests that the grant rate is unlikely to change.

* * *

Senior Research Fellows Danny Chou and Megan Somogyi contributed to this article.

- Happy 175th birthday California! - September 9, 2025

- SCOCA is spending more time writing fewer and longer decisions - August 28, 2025

- Joseph R. Grodin memorial event - August 21, 2025