Justice Chin’s legacy

Overview

On

January 15, 2020, Justice Ming William Chin — the court’s longest-serving sitting

member — announced that he will retire in August. His distinguished, 24-year

tenure has spanned three chief justices and five governors. Former Governor

Pete Wilson, who appointed Justice Chin to the state high court in 1996, praised

him as “a model of judicial excellence.” Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye described

Justice Chin as a “valuable mentor” and stated “his loss to this court

will be incalculable.”

In

this article we analyze Justice Chin’s contributions to California law and reflect

on his remarkable career.

Justice

Chin has been a workhorse

Throughout

his tenure, Justice Chin has been one of the most productive writers on the court.

After his appointment, Justice Chin “quickly gained a reputation for producing

a prolific number of opinions — authoring six majority opinions in his first eight

months.”[1] A 2006 profile described Justice Chin as “one of the

bench’s most active members.”[2]

The

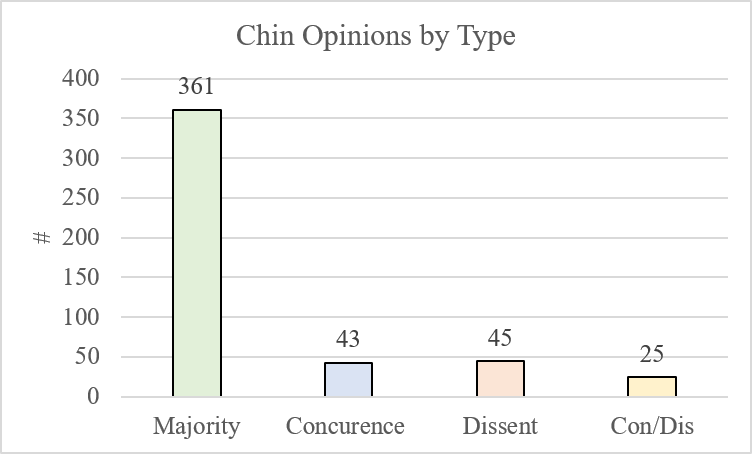

numbers corroborate Justice Chin’s reputation. As of publication, Justice Chin

has written 474[3]

total opinions: 361 majority (76%), 113 separate (24%). He has written a nearly

identical number of concurring opinions (43) as he has dissenting opinions

(45). He also has written 25 concurring and dissenting opinions in which he

concurs in part, but dissents in part from a majority opinion.

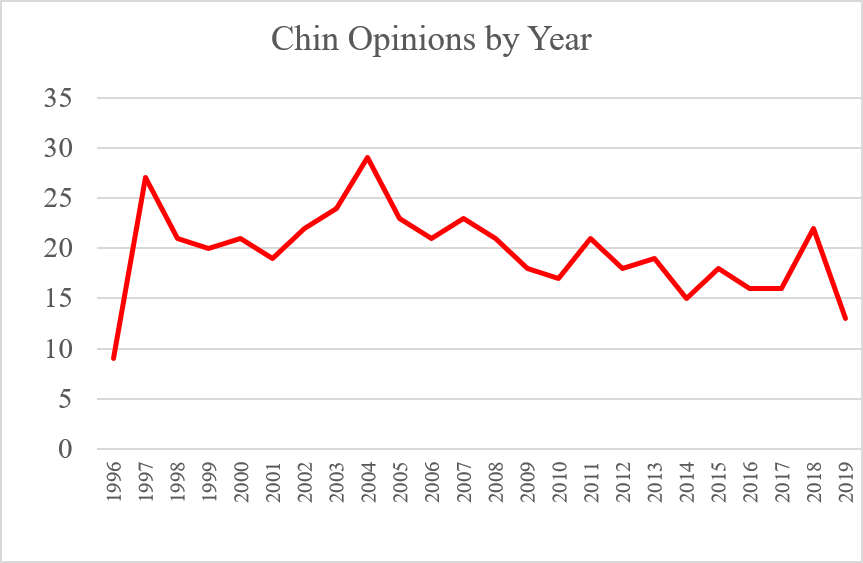

Justice

Chin was especially active during the first half of his career. In his first 12

years, he authored an average of 22.5 opinions per year. In 2004, he authored a

career-high 29 opinions. Justice Chin has also remained productive during the

second half of his career. His 86 opinions since 2015 are second only to

Justice Liu’s 118. He has a career average of 19 opinions per year.

Justice Chin has profoundly shaped criminal

law and labor and employment law

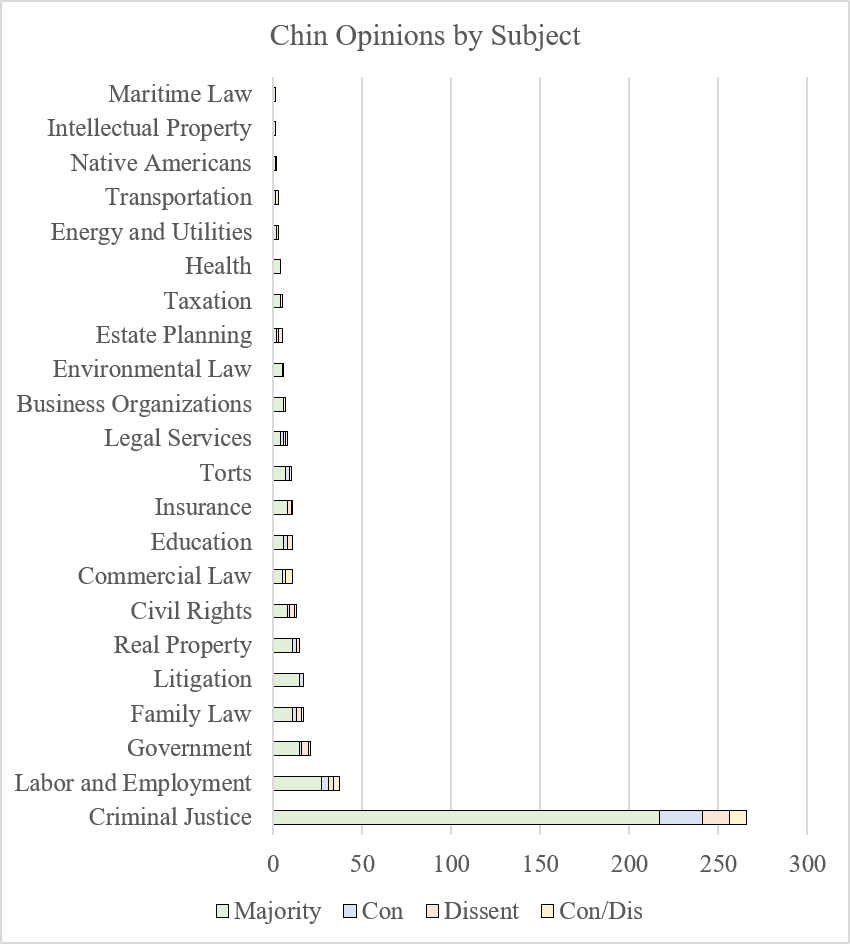

Although

Justice Chin has written opinions on dozens of subjects, his greatest impact was

on criminal law and employment law. This is unsurprising, given that Justice

Chin began his legal career as a prosecutor and has co-authored Rutter Group

practice guides on employment litigation and forensic DNA evidence. We used Westlaw’s

categorizations[4]

to create the following chart.[5]

Justice

Chin has written opinions on 22 different subjects, which demonstrates his

versatility. The data also show that Justice Chin has areas of particular expertise.

Just over half (56%, 266 of 474) of his opinions are in criminal cases. That

percentage is consistent with our previous finding that Justice Chin’s opinions

are weighted slightly toward the criminal side. The plurality of his opinions

in civil cases (17.8%, 37 of 208) address labor and employment. Government (9.6%,

20 of 208) and family law (8.2%, 17 of 208) are his next most frequent civil

subjects.

But

Justice Chin should also be remembered for the quality of his opinions.

Commentators have long lauded his analysis for its insightfulness and clarity. In

criminal and employment cases, Justice Chin often wrote separately to stake out

a nuanced position. In 266 criminal cases, he wrote 49 separate opinions, or about

18% of the time. In two criminal cases — People

v. Cleveland (2004) 32 Cal.4th 704 and Cowan

v. Superior Court (1996) 14 Cal.4th 367 — he wrote both the

majority opinion and a separate concurrence. In 37 labor and employment cases, Justice

Chin wrote 10 separate opinions, or about 27% of the time.

Justice

Chin also authored several landmark opinions that have transformed California law.

His most-cited opinion, Cel-Tech

Communications, Inc. v. Los Angeles Cellular Telephone Co.

(1999) 20 Cal.4th 163, established the “safe harbor” doctrine,

which precludes plaintiffs from suing under California’s Unfair Competition Law

based on actions “the Legislature permits.” That same opinion also established

an unfairness test for a UCL claim between competitors, while leaving in place

multiple other tests for consumer claims. Justice Chin’s most-cited

criminal-law opinion, People

v. Falsetta (1999) 21 Cal.4th 903, affirms the

constitutionality of Evidence Code section 1108. That section permits

prosecutors to introduce evidence of a defendant’s other sex crimes to show

propensity. More recently in Sargon

Enterprises, Inc. v. University of Southern California

(2012) 55 Cal.4th 747, Justice Chin clarified the gatekeeping

function of trial courts in admitting expert testimony.

Justice

Chin’s inimitable judicial philosophy

Although

Justice Chin is the court’s most currently identifiable conservative member, his judicial philosophy

transcends binary political labels. When he was appointed to the high court in

1996, the Los Angeles Times described him as “moderately conservative.”[6] A year later, he voted in

favor of overturning a law requiring parental consent for abortion.[7] Although he is generally conservative

on criminal matters, he notably reversed a woman’s manslaughter conviction

because the trial judge did not allow her to present evidence of battered

women’s syndrome in her defense.[8] And as we previously

noted, “conservative” here is a relative term: Justice Chin only

looks somewhat conservative compared with the court’s other current members;

the usual conservative and liberal labels are not good descriptors for these

justices; and this is a court that has trended back to a median after dramatic

swings to the left and right in the past 50 years.

Justice Chin’s two most recent dissents

— People v. Lopez (2019) 8 Cal.5th 353 and OTO, L.L.C. v. Kho (2019) 8 Cal.5th 111 — are emblematic of his

judicial philosophy. In Lopez (a 4–3 criminal decision) the Brown-appointed majority held that

the Fourth Amendment does not allow warrantless vehicle searches for a driver’s

identification.[9] In

his dissent, Justice Chin thoughtfully discussed the practical consequences of

the majority’s ruling on law enforcement and emphasized the importance of stare

decisis. Justice Chin’s analysis of the majority was sharp: “In brief, the

majority sets up a straw man and then knocks it down, relying on a decision

that is not on point.”[10]

In the labor and employment case Kho, Justice Chin

dissented from an otherwise-unanimous decision to write that an arbitration

agreement was not substantively unconscionable. That Justice Chin dissented

alone is itself noteworthy because nearly 80% of California Supreme Court opinions

in 2018 were unanimous. Dissenting opinions are unusual — solo dissents are

rare. Justice Chin’s dissent in Kho was the only dissent from an

otherwise-unanimous decision in 2019. And Justice Chin’s pointed clarity was

again on display in Kho: “Today, the majority holds that an arbitration agreement is

substantively unconscionable — and therefore unenforceable — precisely because

it prescribes procedures that, according to the majority, have been ‘carefully

crafted to ensure fairness to both sides.’ If you find that conclusion hard to

grasp and counterintuitive, so do I.”[11]

Conclusion

Few justices in the history of the

California Supreme Court leave a legacy as distinguished as Justice Chin. In 24

productive years, he shaped and refined California jurisprudence, especially criminal

and employment law. Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye and Justice Corrigan, both also

former prosecutors, will likely honor Justice Chin’s pro-law enforcement

perspective going forward. But the court will undoubtedly miss Justice Chin’s pro-business

jurisprudence in labor and employment cases. When Justice Chin retires, the

court will also lose a prolific writer with the ability to synthesize complex

legal doctrines into masterful opinions. Overall, Justice Chin should be

remembered for his clarity and courage.

—o0o—

Senior research fellows David and

Michael Belcher are attorneys in private practice and government service,

respectively. Nothing here reflects the views of their employers, and they

write solely in their academic capacity.

[1] Justice Chin also wrote two concurrences during his first

eight months. California Courts Press Release, Justice Ming Chin to Retire from

California Supreme Court (Jan. 15, 2020), https://newsroom.courts.ca.gov/news/justice-ming-chin-to-retire-from-california-supreme-court

[2] See McKee, Judicial Profile: Ming Chin, The Recorder

(May 2, 2006), at https://www.law.com/therecorder/almID/900005452654/judicial-profile-ming-chin/

[3]

We excluded Burton v. Shelley (2003) 2003 WL 21962000 because it is a

writ denial that Justice Chin co-authored with Justices Baxter, Werdegar, and

Brown. We counted People

v. Superior Court (Johnson) (2015)

and its

republication, People

v. Superior Court (Johnson) (2015), as one opinion. In

three cases — People

v. Cleveland (2004),

Cowan

v. Superior Court (1996), and Cheong

v. Antablin (1997)

— Justice Chin wrote the majority opinion and a concurring opinion. We counted

the majority and concurring opinions separately.

[4] We acknowledge the

limitations of Westlaw’s categories. Most cases address multiple areas of law.

And some categories (like “Criminal Justice”) are broader than others.

[5] We categorized Garcia v. McCutchen (1997) as “Litigation” instead of

“Civil Procedure.” We categorized Merrill v. Navegar, Inc. (2001) and Johnson v. American Std., Inc. (2008) as “Torts” instead of “Products

Liability.” We categorized People v. Macias (1997) as “Criminal Justice” instead

of “Juvenile Justice.” We categorized County of San Diego v. State of

California

(1997) as

“Government” instead of “Securities and Commodities.” We categorized Western Security Bank v. Super.

Ct. (1997) and Zengen Inc. v. Comerica Bank (2007) as “Business Organizations.”

Finally, we categorized Sinclair Paint Co. v. State Bd.

of Equalization

(1997) as

“Government” instead of “Business Regulation.”

[6] Maura Dolan, State High

Court Justice Sworn In Amid Protests, LA

Times (March 2, 1996), athttps://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-03-02-mn-42134-story.html.

[7] American

Academy of Pediatrics v. Lungren (1997).

[8] People

v. Humphrey (1996).

[9] We previously identified

People v. Lopez as one of just a few 4–splits with the Brown appointees

in the majority and all three senior justices dissenting.

[10] People v. Lopez (2019) 8 Cal. 5th 353, 382 (dis. opn. of Chin, J.).

[11] OTO, L.L.C. v. Kho (2019) at 141–42 (dis. opn. of Chin, J., citation

omitted).