SCOCA year in review 2019

Overview

The effect a majority of four justices appointed by Governor Jerry Brown might have on the California Supreme Court has been a major question in the past few years. After all, the last time four Brown appointees controlled the court it endured its most chaotic period in the last century. With the fourth Brown appointee (Justice Groban) having completed his first year on the court, we examined the court’s opinions from February 2015 to December 2019 for evidence that such times are upon us again. We found little support for a conclusion that another ultra-partisan-liberal Rose Bird era is dawning — in fact, the evidence so far is to the contrary.

We draw several conclusions:

- The lineup of four justices appointed by Governor Brown and three appointed by other governors has not divided the court. The court rarely decides cases by 4–3 votes in any period. And that rate is lowest in the Groban period.

- The court’s degree of consensus remained relatively stable across all three periods.

- Justices Liu and Chin are mirror-image opposites, so that Justice Chin’s upcoming retirement is potentially the largest factor in Justice Liu’s impact on the court going forward.

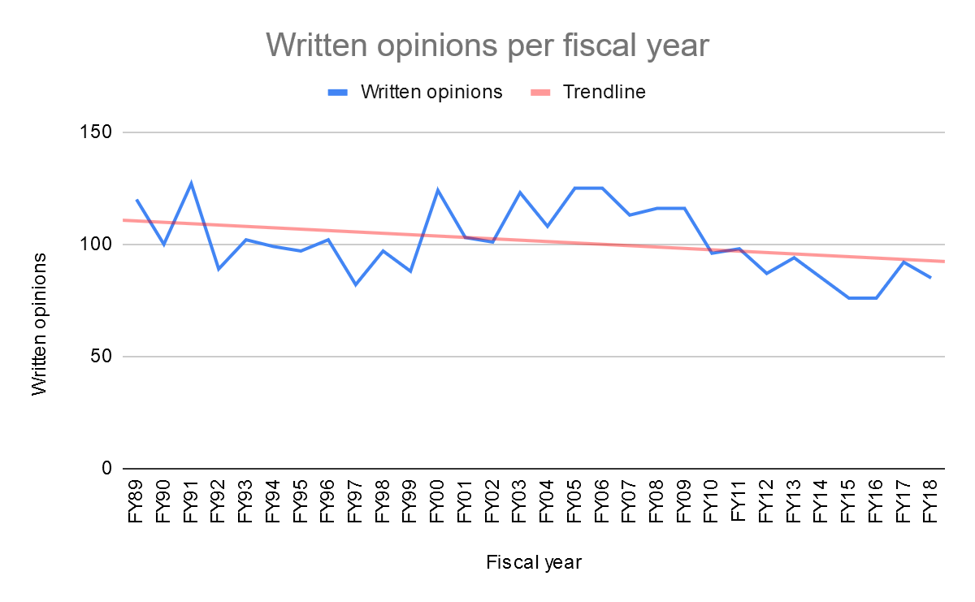

- The court’s opinion output trend remained relatively stable during its pro tem interregnum, in that it continued to decline.

Methodology

We reviewed all opinions published between February 2015 and December 2019. Year-on-year comparisons are inherently arbitrary, so we divided the decisions into three periods.

Period BX (post-Baxter with Werdegar) begins after Justice Baxter’s last vote in December 2014. It runs from the first decision with Justices Cuéllar and Kruger on February 5, 2015 to Justice Werdegar’s last vote on August 31, 2017.[1]

Period WX (post-Werdegar with pro tems) is the thirteen-month period of rotating pro tem justices after Justice Werdegar’s last vote in August 2017. It runs from the court’s first decision with the pro tems filling Werdegar’s seat on November 13, 2017 until the last pro tem decision on March 28, 2019.

Period GX runs from Justice Groban’s first opinion vote on March 28, 2019 through December 2019.

We looked for trends across all those periods. There are 386 opinions: 213 in the post-Baxter period, 111 post-Werdegar, and 62 with Groban. We discarded some cases (en banc decisions, for example).

The justices’ votes are categorized by simple majority vote, concurring and dissenting, concurring, and dissenting; we also counted how many opinions in each category a justice wrote. We counted all votes and opinions in a case.[2] The pro tem justices are counted as one justice. We continue to divide the justices into two groups: senior (the Chief Justice, and Justices Chin and Corrigan) and Brown (Justices Liu, Cuéllar, Kruger, and Groban). As our analysis shows, so far that division is proving illusory.

Analysis

There is no Brown wing — instead, consensus dominates

The 4–3 Brown–senior justice lineup has not divided the court. And the court’s degree of consensus remained relatively stable across all three periods. We looked at three metrics for this: all 4–3 vote splits, number of dissenting opinions, and majority versus non-majority votes.

The court rarely decides cases by 4–3 votes in any period: two in the Groban period, four in the post-Werdegar period, and seven in the post-Baxter period. As percentages of the number of cases, those figures are individually small and relatively close across all three periods.

GX 2/62=3.23%

WX 4/111=3.60%

BX 7/213=3.29%

We were alert for any 4–3 splits in the Groban and post-Werdegar periods, particularly for decisions with the four Brown justices in the majority and the three senior justices in the minority. There were none in the post-Werdegar period, and two in the Groban period.[3] The result: just two Brown v. senior splits in 173 cases decided since November 2017.[4] Those exceptions prove the rule that a reliable bloc of Brown justice votes is (as yet) nonexistent.

The dissent rate changes little across the three periods. If anything, dissents as a proportion of majority opinions is trending downward. The balance of dissents to all opinions is less reliable because Justice Liu’s high number of separate opinions skews the all opinions number higher.

| DISSENTS AS PERCENT OF ALL PERIOD OPINIONS AND OF PERIOD MAJORITIES | |

| GX ALL OPINIONS 80 | 7/80 (8.75%) |

| GX MAJORITIES 62 | 7/62 (11.29%) |

| DISSENTS 7 | |

| WX ALL OPINIONS 155 | 13/155 (8.39%) |

| WX MAJORITIES 111 | 13/111 (11.71%) |

| DISSENTS 13 | |

| BX ALL OPINIONS 307 | 26/307 (8.47%) |

| BX MAJORITIES 212 | 26/212 (12.26%) |

| DISSENTS 26 |

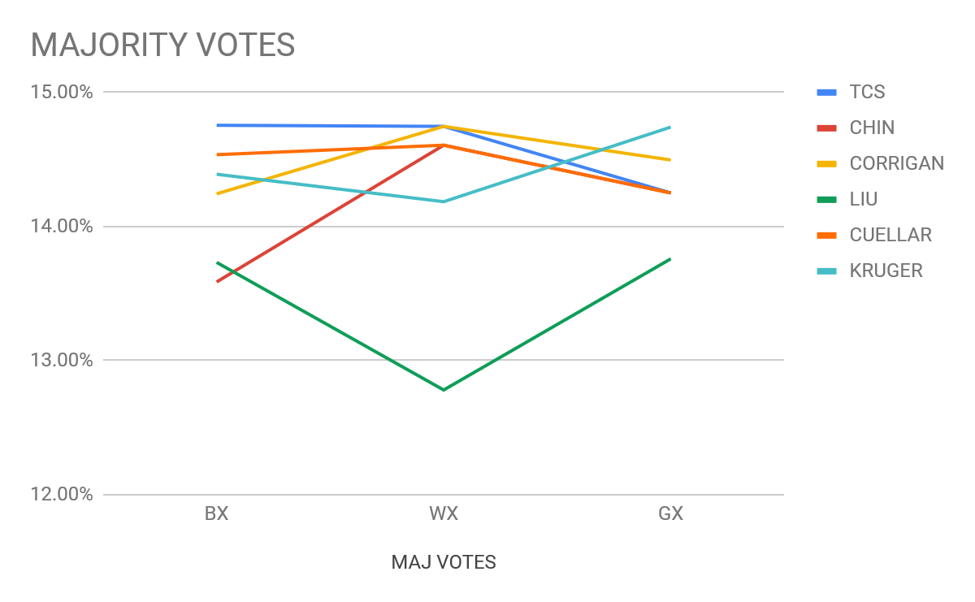

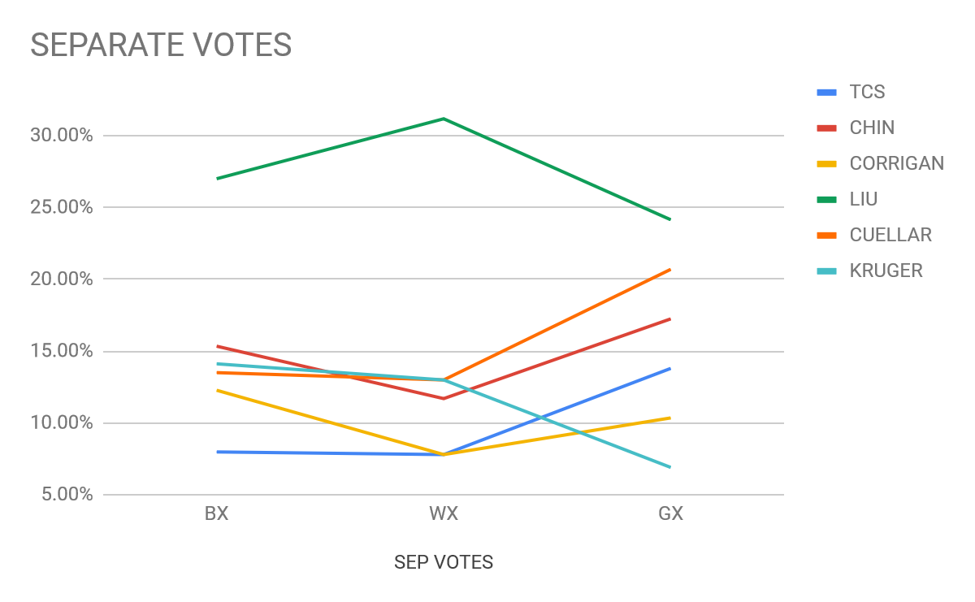

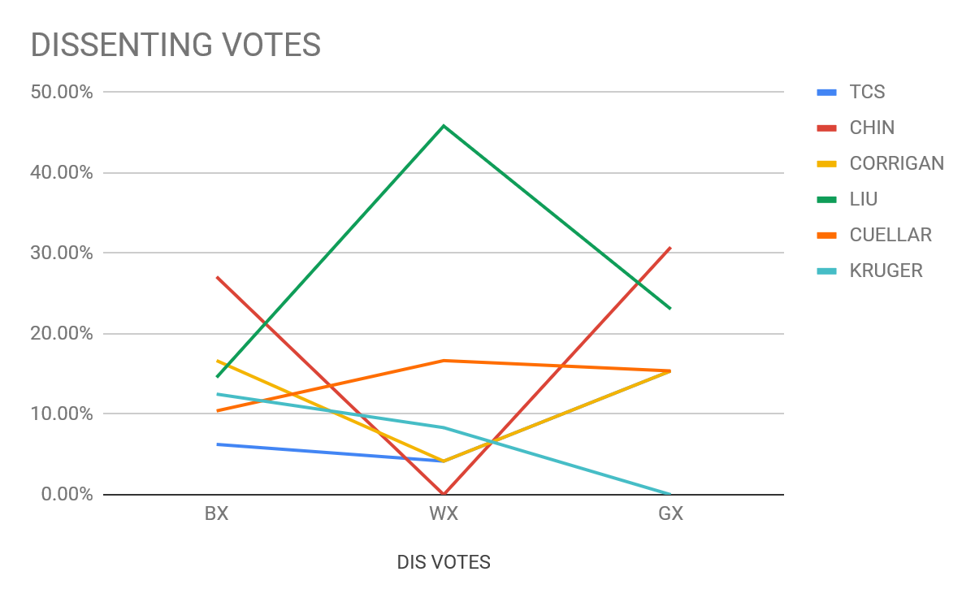

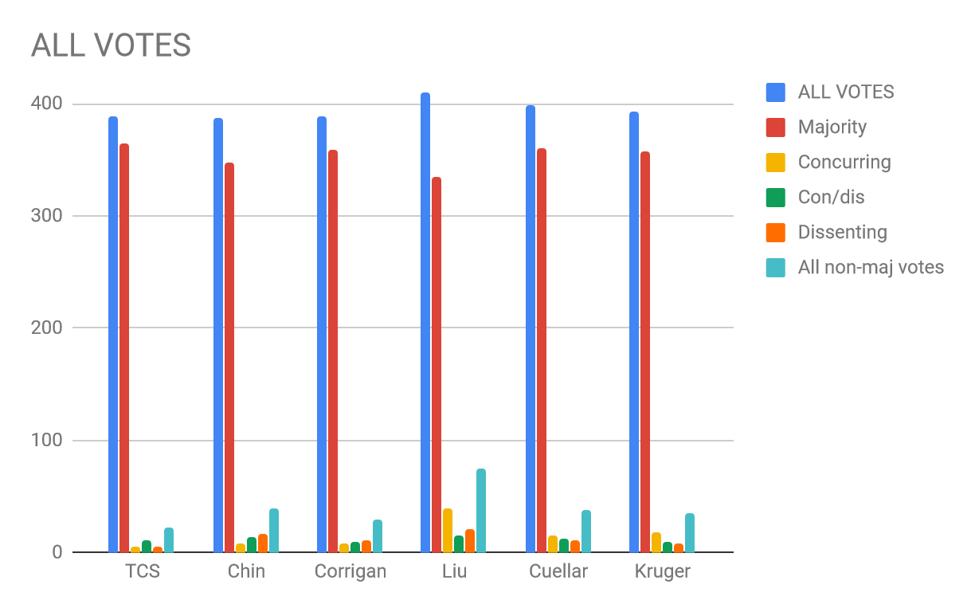

We calculated majority, all separate, and dissenting votes as percentages of all votes in each period, shown below.[5]

The apparent downward trend in majority votes is deceptive because the y-axis scale is so small. Except for Justice Liu, the court shows very little variation in its majority voting rate across the three periods.

We do note a five- to ten-point increase in the rate of separate votes, which is significant. That arguably cuts against our consensus conclusion, because it means that justices are signing more non-majority opinions. This is mitigated by the fact that, as the table below shows, except for Justice Chin there is no corresponding overall upward trend in dissenting votes.

The increase in overall separate voting is less important than the rate of dissenting votes. Discounting Justices Chin and Liu (who cancel each other out, as discussed below), there is no obvious trend in dissenting votes; if anything, the trend line is flat. Coupled with the consistently low proportion of 4–3 divided opinions and the low- and flat-rates of dissenting opinions noted above, we conclude that the court’s decisions are broadly supported by its members.

Although Justice Groban’s voting record has not yet revealed his ideology, the fact of his silence is interesting. Justice Groban authored no opinions in the surveyed period; he filed his first opinion on January 30, 2020.[6] As a point of comparison, Justice Chin authored six majority opinions in his first eight months on the court, and Justice Liu started authoring opinions just 90 days after joining the court.

Comparing the three periods

Period BX, post-Baxter with Werdegar: While the raw number of non-majority votes cast during this era may give the appearance of disagreement among the justices, this is deceptive. A proportional comparison shows that the majority-to-dissent ratio has remained consistent across the three periods. And while there is a greater number of opinions published during this period than subsequently, this likely is explained by the relative lengths of the periods. The post-Baxter era spanned two and a half years, from February 2015 until August 2017. And note that Justice Werdegar cast the greatest number of majority votes (only matched by the Chief Justice at 202) during this period.

Period WX, post-Werdegar with pro tems: The court retained a consistent proportionality with its voting patterns after Justice Werdegar retired. The pro tems joined dissenting opinions (5) more than every other justice except for Liu (11). But otherwise the pro tem justices were remarkably consistent: they voted with the majority almost 90% of the time. And the voting proportionality remained consistent with the previous and following periods.

Period GX, with Groban: Voting remained homogenous after Justice Groban joined the court. Every member (except for Justice Liu) voted with the majority in over 93% of all opinions: Chief Justice 93.54%, Chin 93.54%, Corrigan 95.16%, Liu 90.32%, Cuéllar 93.54%, Kruger 96.77%, Groban 96.67%. And even then Justice Liu, in the majority the least in this period, is at 90%. His voting in period WX (81.98% majority) may be an anomaly, as in the most recent period GX his majority rate better compares to his voting in period BX (88.26%). This may signal a return to normal, and that his usual voting practices were interrupted during the pro tem interregnum. It is too early to more closely analyze Justice Groban given the limited dataset.

Finally, we compared voting patterns for the pro tems and Justice Groban in periods GX and WX. The voting patterns are consistent. Both voted with the majority in 90–96% of cases and cast a non-majority vote in 3–10% of cases. The pro tem majority voting trend likely flows from two factors: pro tem justices mostly sit for only one case.[7] And pro tems should not be the deciding vote in a high court case — note that they authored no majority opinions. The question for this year is whether this voting pattern accurately reflects Justice Groban’s views, or if he will perform differently going forward.

The relative influence of Justices Chin and Liu

Referring to the per-justice vote graphs above, Justices Chin and Liu are mirror images, moving in opposite directions to each other. We read this as indicating high disagreement between these two justices, particularly during the post-Werdegar period.

That led us to consider the impact of Justice Chin’s imminent retirement. It is clear that when the court moves with one of these justices, the other moves in opposition. Without Justice Chin, will Justice Liu pull the court with him? We found conflicting evidence for Justice Liu’s effect on the court.

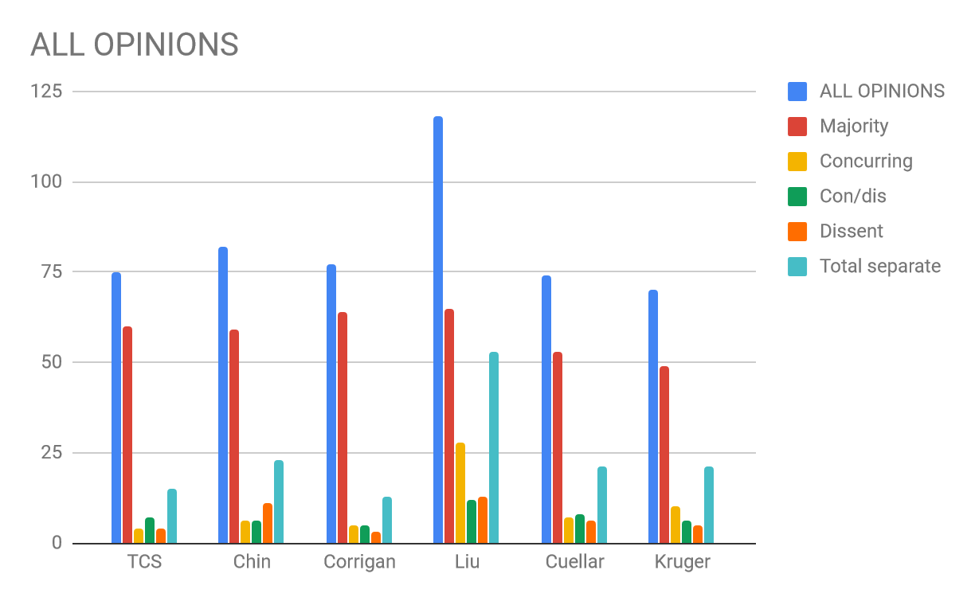

Cumulatively across all three periods, Justice Liu is first in nearly every category — importantly, he authored the most majority opinions. And his share of majority opinions is climbing.

| CUMULATIVE 386 | TCS | Chin | Corrigan | Liu | Cuellar | Kruger | AVERAGE |

| ALL OPINIONS | 75 | 82 | 77 | 118 | 74 | 70 | 82.67 |

| Majority | 60 | 59 | 64 | 65 | 53 | 49 | 58.33 |

| Concurring | 4 | 6 | 5 | 28 | 7 | 10 | 10.00 |

| Con/dis | 7 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 7.33 |

| Dissent | 4 | 11 | 3 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 7.00 |

| Total separate | 15 | 23 | 13 | 53 | 21 | 21 | 24.33 |

| TCS | Chin | Corrigan | Liu | Cuellar | Kruger | AVERAGE | |

| ALL VOTES | 388 | 387 | 388 | 410 | 399 | 393 | 394.17 |

| Majority | 365 | 348 | 359 | 335 | 361 | 358 | 354.33 |

| Concurring | 6 | 8 | 8 | 39 | 15 | 18 | 15.67 |

| Con/dis | 11 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 11.83 |

| Dissenting | 6 | 17 | 11 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 12.33 |

| All non-maj votes | 23 | 39 | 29 | 75 | 38 | 35 | 39.83 |

We also compared the relative percentages of each justice’s majority and total opinion output per period. Again, Justice Liu is the clear outlier: he wrote the most opinions in all three periods, wrote the most majority opinions in the post-Werdegar period, and tied for most majority opinions in the other two periods.

| BX | TCS | Chin | Corrigan | Liu | Cuellar | Kruger | Werdegar |

| ALL OPINIONS 307 | 44 | 43 | 45 | 57 | 39 | 35 | 44 |

| 14.33% | 14.01% | 14.66% | 18.57% | 12.70% | 11.40% | 14.33% | |

| Majority 212 | 34 | 31 | 35 | 30 | 26 | 21 | 35 |

| 16.04% | 14.62% | 16.51% | 14.15% | 12.26% | 9.91% | 16.51% |

| WX | TCS | Chin | Corrigan | Liu | Cuellar | Kruger | TEMP |

| ALL OPINIONS 155 | 19 | 27 | 19 | 41 | 23 | 24 | 2 |

| 12.26% | 17.42% | 12.26% | 26.45% | 14.84% | 15.48% | 1.29% | |

| Majority 111 | 17 | 19 | 16 | 22 | 18 | 19 | |

| 15.32% | 17.12% | 14.41% | 19.82% | 16.22% | 17.12% | 0.00% |

| GX | TCS | Chin | Corrigan | Liu | Cuellar | Kruger | Groban |

| ALL OPINIONS 80 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 20 | 12 | 11 | |

| 15.00% | 15.00% | 16.25% | 25.00% | 15.00% | 13.75% | 0.00% | |

| Majority 62 | 9 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 9 | |

| 14.52% | 14.52% | 20.97% | 20.97% | 14.52% | 14.52% | 0.00% |

But there is evidence to suggest the court will not move toward Justice Liu. He wrote the most separate opinions, which generally indicates less than full agreement with the court. And he has the high or low scores in three key consensus indicators: the fewest majority votes, the most dissenting opinions, the most non-majority opinions, and the most non-majority votes. In general, Justice Liu is in the majority the least out of all the justices.

Finally, we considered that, once Justice Chin retires, Justice Liu will find less to disagree with. But that depends largely on whom Governor Newsom appoints in Justice Chin’s place.

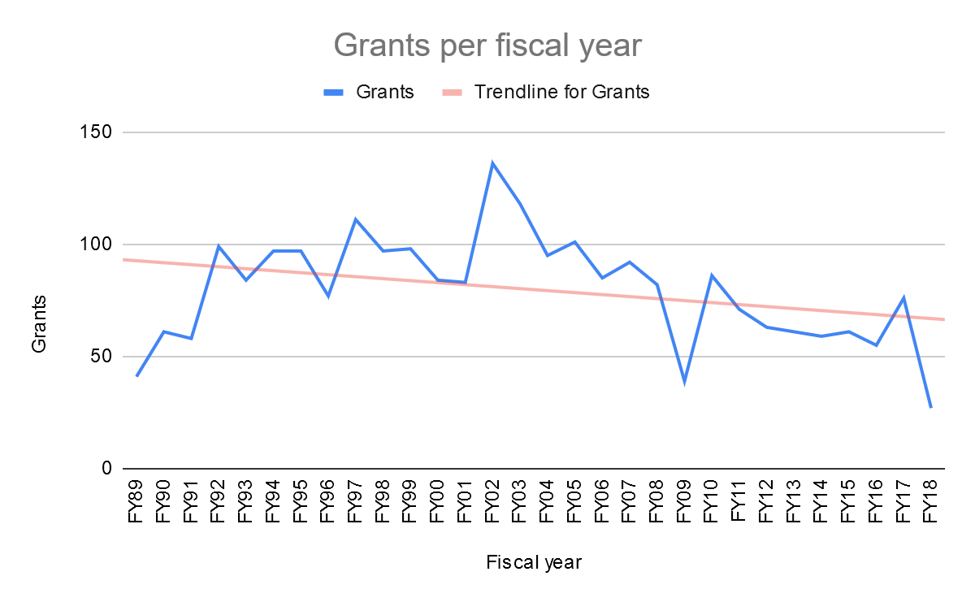

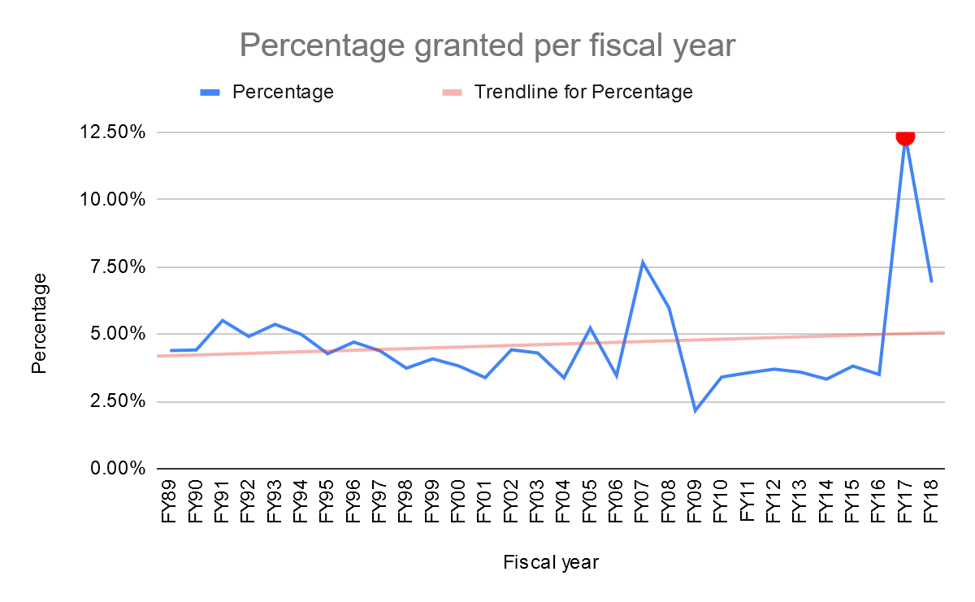

The pro tems did not negatively impact opinion output

The simplest input and output productivity metrics for the court are review petitions granted and opinions written: grants are the cases the court adds to its docket, and issuing an opinion clears a case from the docket. The court’s opinion output trend remained relatively stable during its pro tem interregnum, continuing its gradual downward trajectory. We previously found only weak support for the proposition that the court’s productivity dropped during the pro tem period. Now that Justice Werdegar’s seat has been filled, we can see that the pro tems did not cause the court’s opinion output to drop significantly.

More broadly, these metrics show mixed results for the court as a whole. Two of the above metrics, opinions and grants per year, show declining trends, and the most recent years are all below the 30-year historical averages. The average opinions per year is 101.53, but recent years are all well below 100 opinions. The average number of grants is 79.80, and the trend is below that figure and declining. The percent granted is trending upward, and the two most recent years are above the 4.62% average.[8] The spike in percent granted for FY17 results from the court granting and holding 368 cases in the period of July 2016 to July 2017, increasing its all-grants figure to 489 and increasing the grant rate to 12.35% — all of those figures are by far the highest in their categories in the 30 years of available data since 1988. This spike falls squarely in the BX period (February 5, 2015 to August 31, 2017). Justice Werdegar’s retirement announcement on March 8, 2017 may be a contributing factor.

Justice Chin’s legacy

As detailed in an upcoming SCOCAblog article, Justice Chin has left a lasting impact on the court. He has been a prolific writer from the start of his 24-year tenure on the court, profoundly shaping criminal law and employment law and exhibiting a judicial philosophy that transcends binary political labels. Justice Chin certainly has been a unique voice on the court, and his departure may result in notable change in the court’s opinions and outcomes going forward.

Conclusion

We may see a stable period of membership on the court in the near term. The two remaining senior justices, Justice Corrigan (71) and the Chief Justice (60), look ready to serve at least another decade or two each. The questions we will be looking at this year are who Governor Newsom appoints to replace Justice Chin upon his retirement in August 2020, how Justice Groban integrates with the other members, and whether the court’s consensus model continues to hold.

—o0o—

Senior research fellows Stephen M. Duvernay, Brandon V. Stracener, and

the brothers Belcher, and research fellow Nicholas Cotter all contributed to

this article.

[1] The court decided eight cases with pro tems in the brief period between Justice Baxter’s last vote and Justices Cuéllar and Kruger’s first votes, so we start the post-Baxter period with the first decision they joined in February 2015.

[2] A “majority” vote is when a justice only signs the majority opinion. A justice signing the majority and a concurring opinion is coded as “maj/con” and counts twice: once as a majority vote and once as concurring. Signing a concurring-and-dissenting opinion counts as one vote. Even if an opinion is so titled in Westlaw, we looked at whether the justice concurred in the judgment. Writing a concurring-and-dissenting opinion counts as one opinion. Writing an opinion is counted as a vote for one’s own opinion. So if Justice Liu writes the majority, also writes a concurring opinion, and joins another justice’s concurring and dissenting opinion, that’s three Liu votes for the case (one majority, one concur, one con/dis) and two Liu opinions.

[3] In our 2018 review (written before the pro tem period ended) we found no instances of an all-senior or an all-Brown dissent. It remained true to the end of the pro tem period that there are no opinions in which all justices in each bloc unite against each other.

[4] Interestingly, Justice Kruger siding with the seniors in the majority prevented several would-be 4–3 splits in People v. Aldemat (2019), People v. Armstrong (2019), Hassell v. Bird (2018), and People v. Buza (2018). Note that three of the four are criminal cases, consistent with our previous analysis that Justice Kruger is (so far) the most conservative of the Brown appointees on criminal issues.

[5] Because the time periods are different, the total number of decisions in each period varies widely, and it is not possible to compare raw subtotals for one justice across periods. So we converted each justice’s subtotals to percentages of all opinions or votes in a period and compared those. That permits us to show how a justice’s output changed over time.

[6] K.J. v. Los Angeles Unified School District (S241057) January 30, 2020, 2020 WL 479382.

[7] In period WX, 81 Court of Appeal justices sat pro tem, 26 of them sat twice, and two sat on three cases.

[8] The disparity between the grants and percent granted is because the percent granted includes grant-and-hold and grant-and-transfer. Review granted by the court is a far smaller figure, and it is declining.