SCOCA year in review 2020

Overview

Let’s first agree that 2020 was terrible: a calamitous presidency, raging wildfires, civil unrest, and a once-in-a-century pandemic. Those combined disasters forced California courts into improvise-and-adapt mode, with the Chief Justice and the Judicial Council exercising emergency powers to keep the courts running. Court appearances shifted to video, trial judges conducted spaced-out-and-masked trials, electronic filings and service became standard procedure, and the California Supreme Court itself held remote argument. The business of the courts and the administration of justice continued. And that difficult evolution mostly happened as things usually do in our state courts: quietly, and with minimal drama.

In this article we update our ongoing search for evidence of partisan behavior on the current California Supreme Court. Such behavior featured prominently in voting patterns in the court’s past, but the current period instead features high consensus rates.[1] We still see no evidence of a Brown versus senior justices split; in fact, this year’s data strengthens our previous conclusion that no such split exists — so far.

That qualification is particularly important now: Justice Chin retired in 2020, replaced by Governor Newsom’s first appointee, Justice Jenkins. That seat change could mark the end of the court’s current consensus pattern. Or it may change nothing if the court’s newest member conforms to the current practice. We likely will not know for at least two years. To illustrate, now that Justice Groban has served for around two years, we can say that to this point his voting pattern conforms to the consensus pattern that preexisted him.

Finally, we examine Justice Liu’s effect on the court, and find support for two possible and conflicting conclusions. Justice Liu could be the court’s most influential current member, in the sense that he writes the most opinions and thus has the greatest effect on the law. Or he could be an outlier who garners few votes for his many opinions. Because we cannot reconcile those conflicting views, we conclude that Justice Liu has at least proved to be the court’s most interesting member to study.

Methodology

We reviewed all California Supreme Court merits opinions published between February 2015 and December 2020. Year-to-year comparisons are inherently arbitrary, so we divided the decisions into three periods, marked by changes in the court’s membership. And because our equally arbitrary three periods will soon become less useful, we also parsed annual data. The three periods are:

- Period BX (post-Baxter with Werdegar) begins after Justice Baxter’s last vote in December 2014. It runs from the first decision with justices Cuéllar and Kruger on February 5, 2015 to Justice Werdegar’s last vote on August 31, 2017.[2]

- Period WX (post-Werdegar with pro tems) is the 21-month period of rotating pro tem Court of Appeal justices filling Justice Werdegar’s empty seat. It runs from the court’s first decision with the pro tems on November 13, 2017 until the last decision with pro tems on March 28, 2019.

- Period GX runs from Justice Groban’s first opinion vote on March 28, 2019 through December 2020.

There are 458 opinions in our dataset: 213 in the post-Baxter period BX, 111 post-Werdegar WX, and 134 with Groban GX.

Opinions and votes are categorized as majority, concurring, concurring and dissenting, and dissenting. We counted all votes and opinions in each case.[3] We count the pro tem justices as one justice. We continue to divide the justices into two groups: senior and Brown. The senior justices are the Chief Justice (Schwarzenegger), Chin (Wilson), and Corrigan (Schwarzenegger); the Brown appointees are Liu, Cuéllar, Kruger, and Groban.

We looked for trends across all those periods and specifically at these things:

- The court’s degree of consensus, measured by the number of unanimous opinions, number of 4–3 splits, and the number of dissents.

- Any instances of four Brown versus three senior justices.

- Each justice’s individual productivity.

- How often other justices agree with Justice Liu’s separate opinions.

Analysis

Summary of conclusions

Thus far, there is no Brown court, no liberal–conservative split, and no swing justice. In fact, our California Supreme Court data support none of those common reductive ways of parsing U.S. Supreme Court opinions. Instead, our state high court is the inverse of the federal high court in important ways. Using the political party of the appointing executive as a proxy, the federal high court has a 6–3 conservative majority, while California’s has a 5–2 liberal majority — both of those are roughly equivalent ratios and percent advantages, but with the parties reversed. The federal high court in recent years was closely divided with one justice on the border having a powerful effect as the “swing” justice (Justice Kennedy or Chief Justice Roberts), while the vast majority of California high court decisions are unanimous, with few 4–3 splits and no clear swing justice. Most importantly, our analyses in this and previous years consistently show that consensus dominates the current California Supreme Court and that the partisan behavior that features so prominently in current U.S. Supreme Court decisions (and equally so in past California Supreme Court eras) are simply absent from today’s California high court.

We recognize that our state high court’s dynamics may change soon; maybe when we write this yearly review in January 2022 it will be apparent that this period of consensus was an anomaly. Indeed, the current period is markedly different from the court’s preceding decades, which show the same liberal–conservative partisan voting that characterizes the modern U.S. Supreme Court.[4] Our study period’s end coincides with a change in the court’s membership: Justice Chin retired and was replaced by Justice Jenkins at the end of 2020. Unlike Justice Groban, Justice Jenkins has a long record of prior bench service, so in a future article we will attempt to predict how Justice Jenkins might behave individually and how he might change the court’s behavior. It is possible that our analysis might predict (and more importantly, experience may prove) that substituting a liberal Jenkins for a conservative Chin will weaken or even end the California Supreme Court’s current golden era of consensus.

Justice Liu is the court’s most interesting member to study. There is an argument for him as the court’s most influential member: he writes the most majority opinions and more opinions overall than anyone, so the volume of his contribution to California law is on pace to outstrip justices who have been on the court far longer than he has. There also is an argument that he is the court’s least influential member: he votes in the majority less than any other justice, he dissents the most, and his separate opinions infrequently entice another justice (other than Justice Cuéllar) to sign on — which could indicate that his separate opinions are unpersuasive to anyone else. Our data support both arguments, which is also something unique to Justice Liu: no other justice has such an interesting array of potential interpretations. The upshot is that regardless how you view his position on the court, Justice Liu is its most interesting member to study.

The court’s performance

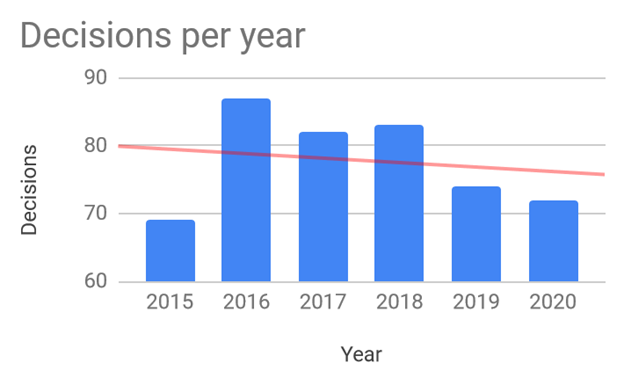

The simplest input and output productivity metrics for the California Supreme Court are review petitions granted and opinions written. Grants are the cases the court adds to its docket, and issuing an opinion clears a case from the docket. Unfortunately, the Judicial Council has not yet published its figures for fiscal year 2019, so we cannot present updated versions of the figures based on the official data. Instead, we present the annual opinions for our sample period.[5]

There is no change in the trend line from our previous analyses. The court’s number of annual merits decisions continues to trend downward at a modest rate. This downward trend in opinion output does not appear to be linked to the number of capital cases decided by the court, as some scholars have argued.[6] For example, the Judicial Council’s annual reports show that in fiscal year 2015, the court wrote 26 opinions in capital cases and 85 opinions overall. In fiscal year 2019, the court wrote fewer opinions in capital cases (18) and still wrote only 85 total opinions.

Comparing individual justice performance across the three periods

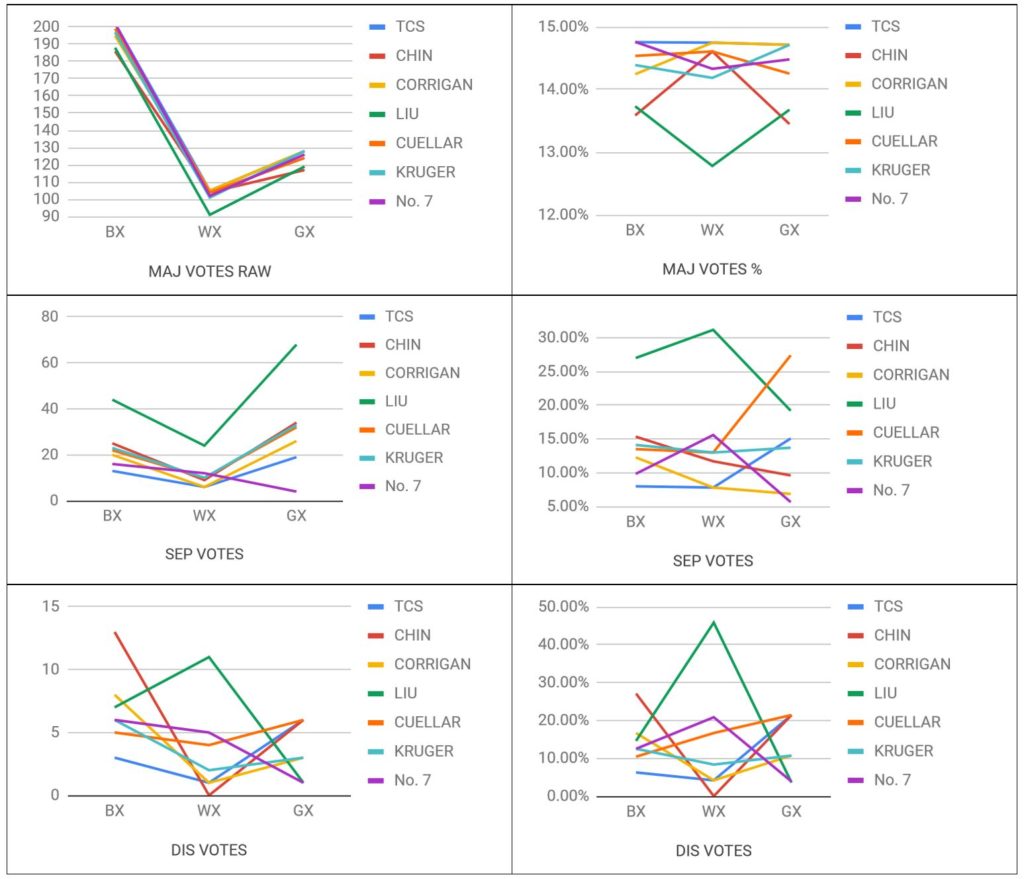

As the graphics below show, we calculated majority, all separate, and dissenting votes, both as raw numbers (the left set) and as percentages of all votes in each period (the right set). Note that we did not include Justice Groban’s opinions in these graphics — in his two years on the court, he authored just eight opinions (seven majority and one dissent). These graphics prove two things: the majority votes for all justices track very closely (indicating a high degree of consensus) — except for Justice Liu, whose voting pattern is a marked departure. The disparity in separate opinions is a good illustration of just how much more Justice Liu writes than the other justices. The graphics displaying the justices’ dissenting opinions show that the number of dissents per justice remains low, with (other than Justice Liu) only small individual variations. We think this corresponds with the majority voting and per-year opinion-writing graphics below, in that all support a conclusion that this court has a consistently high degree of consensus (again, except for Justice Liu).

Other than Justice Liu, the court continues to show very little variation in its majority voting rate across the three periods. Justices Chin and Liu continued to behave inversely across the periods.

Discounting justices Chin and Liu, there is still no obvious trend in dissenting votes. Coupled with the fact that majority votes track closely and the consistently low proportion of 4–3 divided opinions, we conclude that the court’s decisions are broadly supported by its members.

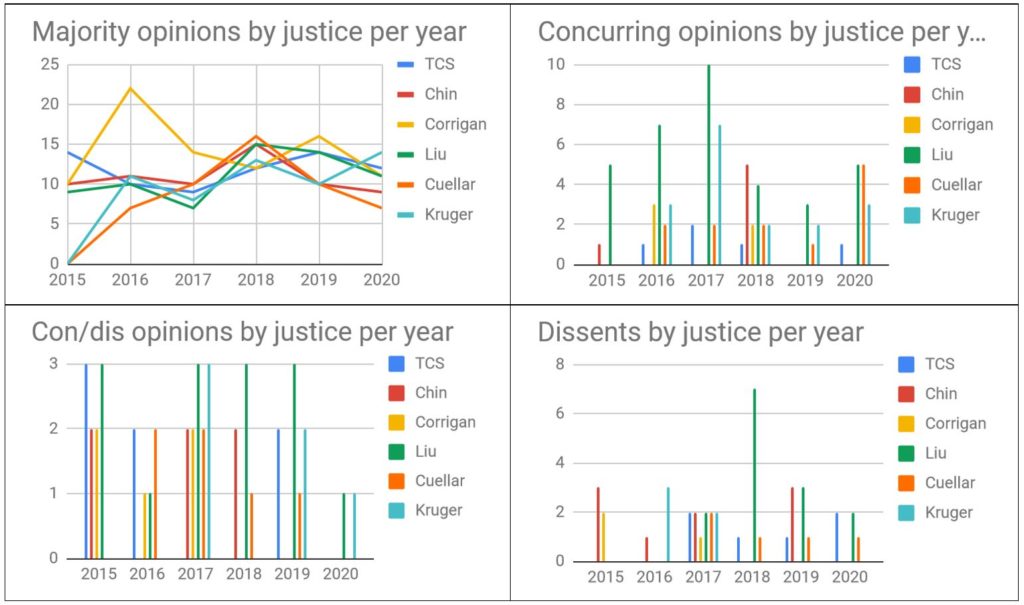

Finally, we also compared the type of opinions written by each justice annually in our six-year dataset.

Comparing opinion type by justice by year supports our conclusion that the court shows strong consensus. We view these results as supporting that conclusion in three ways. One way is that the number of majority opinions per justice per year is converging, which shows that no individual justice or group of justices dominates the court’s merits decisions (this point also bears on our discussion of Justice Liu’s effect below). Next, note the y-axis scales on the separate opinion graphics above — all are very low quantity, showing that anything other than full agreement with the court’s opinion is uncommon. Finally, dissents (except for Justice Liu) occur rarely.

There is no Brown wing — instead, consensus dominates

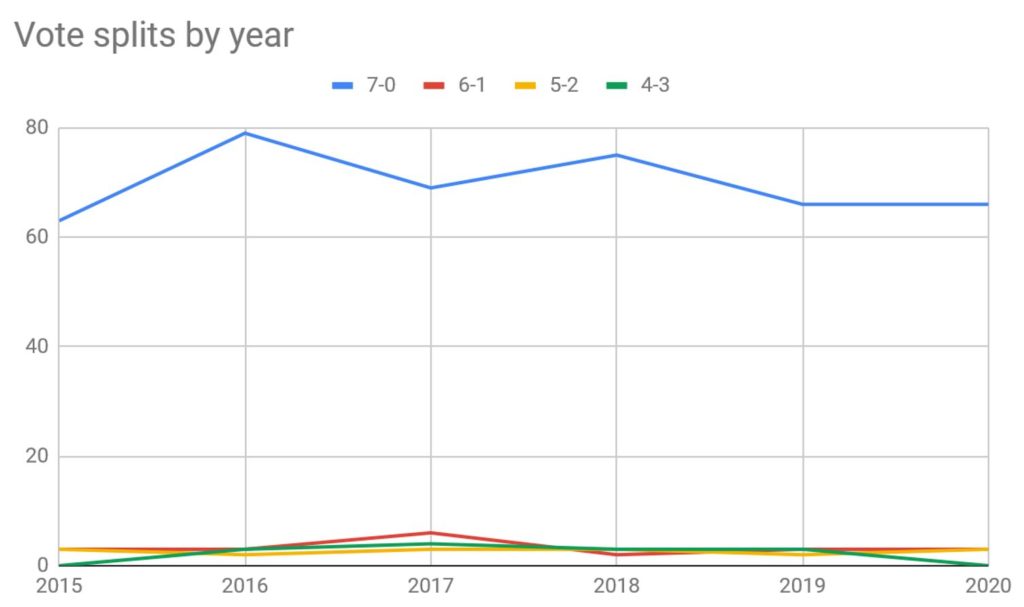

The court’s strong consensus model continues to be apparent, and there is no senior versus Brown division. We looked at three metrics for this: all 4–3 vote splits, majority versus non-majority votes, and the pattern of dissenting opinions.

Because Justice Jenkins did not participate in any 2020 decisions, our dataset still comprises a 4–3 Brown–senior justice lineup. And the court still has not divided along those hypothetical lines. In fact, the evidence against a Brown–senior justice split is even stronger: in 2020 there was just one 4–3 split (in Reilly v. Marin Housing Authority (2020) 10 Cal.5th 583), and zero Brown–senior splits. The total of Brown–senior splits for the entire time in which a Brown majority has existed is two out of 132 cases, or just 1.5%. That’s consistent with the low incidence of 4–3 splits in other periods: four in the post-Werdegar period (3.6%), and seven in the post-Baxter period (3.3%). Indeed, the incidence of 4–3 splits in period GX is lower than the overall rate: there were 13 splits of 4–3 out of the 458 decisions we reviewed (2.8%) versus 1.5% in the Groban period. The upshot is that the court rarely decides cases by 4–3 votes in any period, and that rate is lowest in the Groban period. (Note that these numbers do not include Reilly, which was added after we calculated these figures; adding one case will not change them significantly.)

We also examined the incidence of each possible voting pattern in general (not individually by justice) and counted majority opinions and votes against dissenting opinions and votes. As with our other calculations, this shows very high and stable consensus rates, with the court deciding cases non-unanimously just a few times each year in the past six years. It also shows that the changes in the court’s membership have had little effect on the overall pattern.

As the graphics above show, the uptick in separate and dissenting votes individually and as compared with majority votes does not show divergence among the justices. Instead, their majority voting rates move in lockstep; their separate votes similarly show low and corresponding change rates; and increases in their dissenting votes show no pattern.

The one indicator we found of a possible Brown–senior split was when we sorted the court’s opinions according to full or partial dissents by Justice Liu. Doing so reveals that the senior justices are always in the majority when Justice Liu dissents in whole or in part, and that if anyone joins him it will only be a Brown justice. That is true for the current GX period, and also in periods WX and BX if we group the pro tems and Justice Werdegar with the Browns. Yet we found only three instances of a Justice Liu dissent that split the court 4–3: two in period WX (in both cases the co-signers were Justice Cuéllar and pro tem Justice Perluss) and one in period BX (co-signed by justices Werdegar and Cuéllar).

With that exception, all of our calculations, both for the three periods and the most recent six years, tell the same story: this court decides cases as a body, by consensus, not based on a group of justices having four votes. This is a marked contrast to the court’s long period of partisan voting from the 1950s to the recent past. One possible factor contributing to this unanimity is the court’s internal operating procedures, which make opinion drafting a pre-argument deliberative process. Before oral argument in each case, the justice charged with authoring the majority opinion circulates a draft opinion or “calendar memo” to the other justices. The other justices provide feedback on the calendar memo to the author, who can incorporate the justices’ suggestions into the opinion.[7] This editing process potentially can gather votes and increase consensus.

The Justice Liu effect

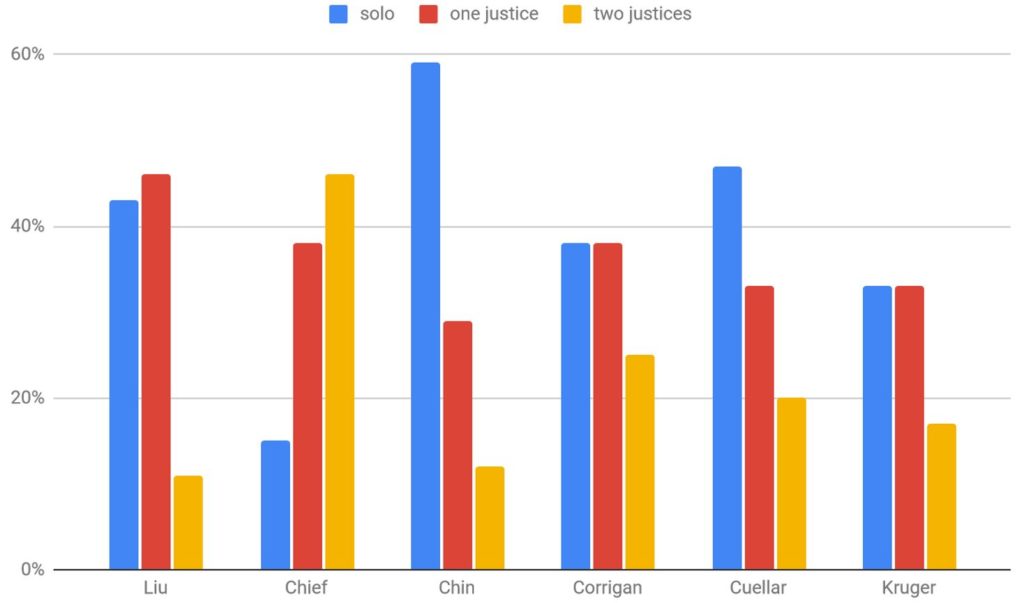

Justices Chin and Liu continued to present as mirror images, moving in opposite directions to each other. We read this as indicating high disagreement between these two justices, particularly during the post-Werdegar period. In comparing the relative effects these two justices had on the court, we found that the data surrounding Justice Liu’s separate opinions can be interpreted in two conflicting ways. Justice Liu’s many separate opinions could indicate that he is influencing the court and the law even when he is not in the majority. Or his separate opinions could reflect only his personal thoughts, nothing more. (We also consider a third scenario below.) So we examined how often other justices agree with Liu’s separate opinions and compared that with how often other justices attract signatures on their separate opinions. The graphic below shows how many times a justice wrote separately alone, with one other justice signing, and with two other justices signing. (We found no instances in our sample period of three other justices signing a separate opinion.)

Justice Liu most often writes separately either alone or with one cosigner. (Note that for this analysis we looked only at con/dis and dissenting opinions. When we say that Justice Liu most often writes “separately either alone or with one cosigner,” this is true only with respect to dissenting opinions or concurring and dissenting opinions. If concurring opinions were included the data would, for example, include cases like In re A.N. (2020) 9 Cal.5th 343, where Justice Liu wrote a concurring opinion joined by four other justices, including the Chief Justice.) That cosigner is most likely to be Justice Cuéllar, who accounts for one-third of the second signatures on Justice Liu’s con/dis and dissenting opinions: 32% overall, 33% of the dissents, and 31% of the con/dis opinions. Of the court’s current membership only the three Brown justices have signed Justice Liu opinions dissenting in whole or in part: Cuéllar (nine times), Kruger (three times), Groban (once); in period WX, five pro tem justices co-signed, and in period BX Justice Werdegar signed once. We did not find any co-signatures by the Chief Justice or justices Chin or Corrigan.

There is evidence suggesting that Justice Liu is influencing the court. Cumulatively, Justice Liu continues to be first in nearly every category: most majority opinions, most concurring opinions, most concurring and dissenting opinions, and most dissents. The graphic above shows that his separate opinions had the highest incidence of one other justice signing. And with Justice Chin’s retirement, Justice Liu’s influence may increase. Justice Liu wrote a dissent against at least one majority opinion from every other justice. Of Justice Liu’s 15 dissents, ten were against majority opinions written by senior justices: six against the Chief Justice, three against Justice Chin, and one against Justice Corrigan. And recall that Justice Liu’s dissents have only been co-signed by Brown justices. Finally, as the voting graphics above show, individually Justice Liu’s majority votes are increasing and his dissenting votes are declining. Those trends could suggest that he and the rest of the court are finding broader agreement. And adding Justice Jenkins might tilt consensus-based majority voters (who ordinarily would not join Justice Liu’s concurrences) toward generating a new majority with a broader holding and no counterbalancing concurrence.

But there also is evidence to suggest the court will not move toward Justice Liu:

- In general, Justice Liu is in the majority less often than any other justice. He wrote the most separate opinions, which indicates less-than-full agreement with the court.[8] And he has the high or low scores in several key anti-consensus indicators: he casts the fewest majority votes (about 15.79% of the subtotal); he dissents the most (around 32% of all dissenting opinions); he writes the most non-majority opinions (about 37% of the total); and his separate opinions attract the least second signatures.[9]

- As the “majority opinions” graphic above shows, Justice Liu’s performance changes over time: Justice Corrigan wrote the most majorities in period BX; Justice Liu wrote the most majorities in period WX; and they tied at 24 each in period GX. Although Justice Liu wrote the most majority opinions overall at 76, Justice Corrigan is only one behind at 75. And those two justices each account for approximately 18% of all majority opinions in our sample period: Justice Corrigan at 18.16%, and Justice Liu at 18.40%. If authoring many majority opinions is an influence metric, on that score the two are effectively tied for the entire study period.

- Although Justice Liu’s dissents are declining, his separate votes and opinions are trending up — far more so than any other justice — while his majority opinions and votes remain relatively flat. Combined with the other evidence we reviewed here, these facts also support the conclusion that when he acts separately from the majority, Justice Liu acts alone, or at most with one other justice (probably Justice Cuéllar). But (as we discuss below in our alternate scenario) the x-factor is whether justices Kruger or Groban (or both) will join if Justice Jenkins does — making Justice Liu’s opinion the majority.

Justice Chin’s retirement presents a major open question for the Justice Liu effect. As we noted last year, in our time periods Justices Chin and Liu operated inversely in dissent: one’s trend increases while the other’s decreases. That’s true both for dissenting votes (as a raw number) and majority votes (as a percent of the period subtotal). We do not imply that the two were mortal ideological opposites — each signed plenty of the other’s majority opinions. The data are only clear that these two justices almost never disagreed together.[10] If Justice Chin dissented, Justice Liu was almost always in the majority, and the reverse was true. No one knows whether Justice Jenkins will continue that role, and any ideological shift he presents could potentially create enough momentum to coax other justices — who thus far have preserved the consensus appearance of joining the majority opinion without comment — into joining Justice Liu’s separate opinions or even creating a new majority. Conversely, Justice Chin’s retirement could lead to even greater consensus on the court. Justice Chin wrote more solo, separate opinions than any other justice during our study period. If Justice Jenkins dissents less frequently than Justice Chin, we might see even more unanimous opinions.

We also considered a third possible interpretation. In this alternate scenario, Justice Liu’s separate opinions are neither useless nor influential. Instead, they have subtle effects of both narrowing and clarifying the majority opinion, and they may provide a means to track changes in the law going forward.

- When he writes separately (particularly when concurring, his largest outlier) Justice Liu’s opinion might cause changes in the majority opinion. The lack of signatures on his separate opinions does not necessarily show disagreement with him — another justice might agree with Justice Liu but still see a higher value in not joining that concurrence. The rationale could be that the majority is agreeable enough, and too many justices joining the concurrence would dilute the majority opinion with a narrower 5–2 or 4–3 vote margin. And the majority opinion’s author might modify that opinion to narrow its holding or otherwise make it more acceptable to another justice who might otherwise sign the concurrence.

- Justice Liu’s concurrences can help observers see the majority opinion’s limits by illuminating a gap between the actual holding and what it could have been. Those separate opinions may help observers understand the boundaries between the court’s actual holdings and the position staked out by Justice Liu. That clarity helps parse opinions from a consensus-driven court that can produce narrow holdings.

- Before he retired, Justice Chin’s opposition to Justice Liu could have limited majority opinions to narrower grounds, both to draw a signature from one of those justices (recall that they never dissented together) and to avoid diluting decisions into difficult-to-parse plurality opinions. Justice Chin’s absence could result in continued consensus but with broader holdings. To the extent justices more frequently sign onto Justice Liu’s future concurrences, observers may see the law moving with him over time. This possibility cautions against reading too much into how few justices join Justice Liu’s concurrences today, because a culture of consensus might cause a justice who otherwise agreed with the concurrence to avoid joining. But Justice Liu’s opinion might change from a two-justice concurrence to a four-justice majority with Justice Cuéllar (who signs most frequently), Justice Jenkins replacing Justice Chin, and one other justice who previously agreed but refrained out of respect for consensus.

Thus, in this alternate scenario Justice Liu’s concurrences affect the court’s holding even without influencing the law itself: they change the substance of majority opinions; show the holding’s limits; and evidence changes in the law.

In attempting to clarify Justice Liu’s effect on the court, we found instead more conflicting evidence. Our data are almost equally susceptible to two opposing conclusions: Justice Liu could be the court’s most influential current member, or he could be an outlier whose many separate opinions have little substantive impact. And we considered an alternate scenario of subtle effects. We cannot reconcile those conflicting views. The only thing our analysis proved is that Justice Liu is the court’s most interesting member to study, and that Justice Chin’s retirement could result in anything from a mild to substantial ideological shift in the court overall.

Conclusion

We predicted last year that the court might see a stable period of membership, and we continue to hope that prediction comes true. Neither of the two remaining senior members, the Chief Justice (61) or Justice Corrigan (72), has expressed an intent to retire. The Chief Justice is up for retention next year in the 2022 election. Justice Corrigan was retained in 2018, so her next retention election will be in 2030. The questions we will look at this year are how Justice Jenkins integrates with the other members, whether Justice Groban will write more opinions, and whether the court’s consensus model will continue to hold.

—o0o—

Senior research fellows Stephen M. Duvernay, Brandon V. Stracener, and the brothers Belcher contributed to this article.

This article was updated on 17 Feb 2020. It now includes Reilly v. Marin Housing Authority (2020) 10 Cal.5th 583. In our defense, Westlaw incorrectly depicts the signatures on that decision; the slip opinion shows that justices Liu, Cuéllar, and Groban signed Justice Chin’s majority opinion, and justices Corrogan and Kruger signed the Chief Justice’s dissenting opinion. We also rephrased our discussion about Justice Liu most often writing “separately either alone or with one cosigner” to clarify that this is true only with respect to dissenting opinions or concurring and dissenting opinions.

[1] A recent analysis of the court’s 1911–2011 voting patterns showed strong patterns of partisan voting beginning in the 1950s. Mark Gergen, David A. Carrillo, Kevin Quinn, and Benjamin Chen, Partisan Voting on the California Supreme Court (2020) 93 S. Cal. L.Rev. 763.

[2] The court decided eight cases with rotating Court of Appeal justices sitting pro tempore in the brief period between Justice Baxter’s last vote and justices Cuéllar and Kruger’s first votes, so we start the post-Baxter period with the first decision they joined in February 2015.

[3] A “majority” vote is when a justice only signs the majority opinion. A justice signing the majority and a concurring opinion is coded as “maj/con” and counts twice: once as a majority vote and once as concurring. Signing a concurring-and-dissenting opinion counts as one vote. Even if an opinion is so titled in Westlaw, we looked at whether the justice concurred in the judgment. Writing a concurring-and-dissenting opinion counts as one opinion. Writing an opinion is counted as a vote for one’s own opinion. So if Justice Liu writes the majority, writes a concurring opinion, and joins another justice’s concurring and dissenting opinion, that’s three Liu votes in the case (one majority, one concur, one con/dis) and two Liu opinions.

[4] See Gergen et al., Partisan Voting on the California Supreme Court (2020) 93 S. Cal. L.Rev. 763

[5] Note that the Judicial Council uses a fiscal year, and we use calendar years, so the respective per-year opinion numbers will be slightly different.

[6] See Goodwin Liu, How the California Supreme Court Actually Works: A Reply to Professor Bussel (2014) 61 UCLA L.Rev. 1246, and Daniel J. Bussell, Opinions First — Argument Afterwards (2014) 61 UCLA L.Rev. 1194.

[7] See Liu, 61 UCLA L.Rev. at 1256.

[8] We use the minimalist phrase “less-than-full agreement” deliberately. Writing separately also signals greater willingness to voice this less-than-full agreement, in contrast with other justices who might be more concerned with preserving the court’s consensus model. Writing separately is a departure from the court’s current norms, at least more so than was true during the court’s partisan period.

[9] Note that for these full-period figures we are using a subtotal that does not include the “Justice No. 7” seat because it was variously occupied by Justice Werdegar, a series of pro tems, and Justice Groban. Due to that rotation, and especially due to the pro tems, the full-period figures for Justice No. 7 are aberrant, so we discard that seat’s figures for some calculations.

[10] We found just one exception in our dataset: People v. Gonzales (2017) 2 Cal.5th 858, where Justice Corrigan wrote the majority, signed by the Chief Justice and justices Cuéllar, Kruger, and Werdegar; Justice Chin wrote a dissent joined by Justice Liu.