SCOCA year in review 2021

Overview

Our review of the California Supreme Court year in 2021 will focus on the court’s immediate future, and we see two possible viewpoints there. From one perspective the court is in harmony, with only incremental changes on the horizon. We still see no evidence on the current court of the partisan behavior that characterized voting patterns in its past, consensus continues to dominate, and there is no evidence of a Brown versus senior justices split. Yet from another perspective the court is primed for change, and that potential for change is our primary concern here.

Analysis

The court’s performance suffered in the pandemic’s second year

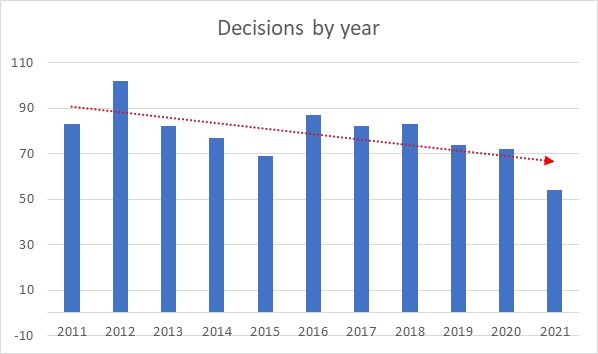

We looked at the simplest metric for the court’s performance: its decision output. As in the past, we use our own annual counts of the court’s decisions instead of the Judicial Council fiscal year figures or the court’s own September-to-September cycle. Thus, the respective per-year figures between those three data sets may be slightly different.

In conversation with The Maddy Institute in November 2021 the center noted that the court was off pace to match its annual average of about 80 decisions. That proved to be true: the court issued 54 merits decisions in 2021, the lowest yearly total in the past decade.

This shows that the pandemic did impact the court’s output, but it was a delayed effect. Over the past two years we focused on decision output as one measure of the pandemic’s effect on the court. The court’s output in the first pandemic year (72 decisions in 2020) is nearly identical to its output the previous year (74 decisions in 2019), showing that the pandemic had no immediate effect on the court’s decisions.

But there is a substantial drop-off between the first and second pandemic years: the court decided 54 cases in 2021, down 28.57% from the 72 decisions in 2020. We suspect this delayed effect stems from an internal opinion-drafting process that sees many of the court’s decisions percolating for a year or more — the 72 decisions issued in 2020 were in the pipeline before the pandemic hit, and the pandemic-related productivity reduction only began to appear later. Many news reports about the court and public comments from the Chief Justice detailed the pandemic-related practical issues the judicial branch struggled with, as did we all. It will not be surprising if 2022 is another low-output year, and it may take another year or so for the court to recover.

Two other factors here are the arrival of Justice Jenkins and Justice Cuéllar’s departure. The minor factor is that Justice Cuéllar served almost to the end of 2021, and he missed just five decisions, which is about 10% of the court’s total decisions. The major factor is that Justice Jenkins replaced Justice Chin — changing a seat naturally disrupts that chambers’ workflow and in turn impacts the court’s overall output. Even Justice Liu’s first majority opinion did not arrive until eight months after he joined the court. So it’s no surprise that Justice Jenkins authored only three opinions, and that those arrived late in 2021. In 2022, other than the pandemic possibly subsiding the other factor that may contribute to lower decision output is the similar gearing-up time for Justice Cuéllar’s replacement (more on that below).

One surprise was the fact that the Chief Justice wrote the most majority opinions in 2021. That’s the first time she wrote the most majorities in a year (in 2012 she tied with Baxter). Adapting the courts to the pandemic while writing the most majority opinions is a prodigious feat.

A brief look at own-motion grants

We also looked at the court’s recent practice with own-motion grants. In the Maddy Institute conversation we noted that the court granted review in People v. Martinez (S267138) on its own motion. Own-motion grants are one uncommon way for a case to arrive on the SCOCA docket. Petitions for review and automatic capital review are the most common, and everything else is rare: original writ proceedings, original jurisdiction, and own-motion grants.

The general principle here is that (other than automatic capital verdict review) Rule of Court 8.512 gives the court substantial control over its docket. The own-motion grant occurs under subdivision (c)(1), which authorizes the court to grant review even if no petition is filed. And under subdivisions (c)(2) and (d), the court can deny a petition and do something else with the case: review it on the court’s own terms, grant and hold, or transfer on its own motion under Rule 8.552.

One or two own-motion grants per year is not unusual: the 34-year average is 2.03 per year. So the single own-motion grant in 2021 is below average. But there are seven years after 2010 with four or more own-motion grants and none before then, and no years without at least one since 2002, so it’s arguably become more frequent. The availability of own-motion grants is yet another way in which California’s high court may exercise its discretionary review powers to oversee and direct how California law develops. This year was not notably different for the court in this respect.

The conventional wisdom is still wrong

The conventional wisdom assumes that justices appointed by Governor Jerry Brown will vote as a bloc, and that California’s high court is as divided along partisan lines as the nation’s high court. Our analysis from 2015 through 2021 disproves both assumptions: the court’s average unanimity rate in that period is 89.74%, and there are no consistent blocs in the rare 4–3 splits. A Brown wing never materialized — instead, consensus dominates. That led us to consider, in the next section, the broader implications of Governor Jerry Brown’s SCOCA appointments.

This period of consensus may be a modern anomaly; yet it continues. Considering the court’s entire history, this consensus model is arguably a return to form. For that history we rely on a 100-year study, which shows that before the 1950s the court’s justices had greater consensus and little partisan voting, and strong patterns of partisan voting beginning in the 1950s. That pre-1950s pattern reflects the court’s current model, which suggests that the partisan liberal and conservative periods from around 1960 to 2010 may have been deviations from the norm. Of course, it is always possible that changes in the court’s membership can upset its equilibrium, and we move to that topic next.

Changes in the court’s membership

We took a macro view of the court’s membership and Governor Brown’s appointments. First, our prediction last year that the court might see a stable period of membership was proved wrong when Justice Cuéllar departed in October 2021. That opening gave Governor Newsom his second appointment: we welcome Justice Patricia Guerrero, nominated by the governor on February 15, 2022. Those events make it difficult to analyze the court’s inter-justice performance, with its membership in flux. For example, there’s too little data to evaluate how Justice Jenkins (who started participating in cases in early 2021) will perform as an individual, or how he will relate with his colleagues. And one faces the same problem with needing time to see how Justice Guerrero compares with Justice Cuéllar.

Another factor is the discussion around Justice Kruger as a finalist for appointment to Justice Stephen Breyer’s position on the U.S. Supreme Court; that discussion alone elevated her profile to the point that she could receive other enticing offers and create another SCOCA vacancy. And this year Justice Corrigan turns 74, and Justice Jenkins turns 69 — both could retire before Governor Newsom’s likely second term ends in January 2027. The upshot is that Governor Newsom might make several appointments, potentially leaving office with a 4–3 majority of the court’s justices.

That would be a surprising reversal for Governor Brown, who after both governorships left office with a 4–3 majority of his appointees serving. Many speculated about how the second Brown court would behave — would it resemble the first Brown court? Surprisingly, the better comparison may lie in how brief their tenures were: the second Brown court’s tenure was even briefer than the first. The first Brown majority ended after about six years (1981–86); the second four-justice Brown majority existed for just two years (2019–21). That parallel is a powerful counterargument to claims about the enduring legacies of Governor Brown’s appointments. Instead, it may be that his majorities were fleeting and their effect was temporary.

Yet viewing a governor’s legacy and the court’s justices this way might be an overstatement because relatively higher turnover is expected on a court that lacks lifetime appointments. The average service of the court’s past 114 justices is nine years. On average a justice has retired every year or so for the past decade: Cuéllar in 2021, Chin in 2020, Werdegar in 2017, Baxter and Kennard in 2014, Moreno in 2011, and George at the end of 2010. That’s 100% turnover in ten years. Only three current members have at least a decade of experience on the court: the Chief Justice, Justice Liu, and Justice Corrigan (the most senior member, appointed in 2006). Contrast that with the justices who served before 2011: Chief Justice George and justices Chin, Werdegar, Baxter, and Kennard each served over 20 years on the court, and they served together for around 15 years. Given the nine-year average service, the George court looks anomalous. As with the court’s return to its pre-1950s nonpartisan model, the current dynamic of frequent departures may be a return to the norm.

Finally, there’s a normative judgment here. Someone like Governor Brown might view frequent turnover, short terms, and brief overlap among the justices as a benefit. That dynamic arguably brings fresh perspectives on a regular basis and prevents stasis. The contrary, more traditional view is that a primary role for the state’s high court is to bring stability and consistency to the law, a role that is undercut by high turnover and its accompanying disorder. And any given governor likely will have little choice between those views because open seats are largely created by forces outside a governor’s control. Governor Brown, with his 11 appointments, benefited both from his 16 years in position and from the luck of the draw. The takeaway is that it’s difficult for any governor to have a lasting impact on California’s high court, and unlikely that any group of justices will persist.

Conclusion

Regardless of what philosophy about judicial appointments Governor Newsom proves to hold, we think it unlikely that any changes in the court’s membership in the next few years will impact its consensus decision model. Given the prospects of a second Newsom term, it would be surprising if any new member could substantially change the court’s dynamics between now and the next open gubernatorial election in 2026. This year we will look for the Chief Justice and justices Groban and Jenkins to be retained in the November 2022 election, observe how Justice Guerrero integrates with the court, and hope for an end to the coronavirus pandemic’s acute phase.

—o0o—

Senior research fellow Brandon V. Stracener contributed to this article.