Analyzing Fourth District Court of Appeal Justice Guerrero

Overview

This article is not about Chief Justice Patricia Guerrero. Nor is it about Associate Justice Patricia Guerrero of the California Supreme Court. Instead, it is about the Justice Patricia Guerrero who sat on the Court of Appeal, Fourth District, Division One from December 2017 to March 2022. For this article we analyzed all merits decisions that Justice Guerrero participated in and looked for trends. We found nothing unusual. Instead, we learned that Justice Guerrero was a typical modern California appellate justice: her opinions had a high unanimity rate, she often voted with her colleagues, and she reversed consistently with the appellate courts overall. The important takeaways here are that the state’s next chief justice could not be described as an outlier; she instead exhibited clear majoritarian behavior and was restrained in the rare instances of disagreement.

Methodology

We searched Westlaw and Lexis for all Court of Appeal cases (published and unpublished) with Justice Guerrero’s name. After discarding junk results we ended with a list of 1,015 decisions in which Justice Guerrero either voted or wrote an opinion; one was per curiam, so call it 1,014. We coded all votes, opinions, case types, and results. Votes and opinions were assigned the center’s standard majority, concur, con/dis, and dissent codes. Case types were civil, criminal, and habeas. Results were affirmed, reversed, and partial (any judgment reversed in part and affirmed in part), and for certain figures below we broke the civil and criminal results into subcategories. In the analysis underlying some figures we omitted cases that did not fit the coding or were outliers. For example, we mostly excluded a small set of case results (appeal dismissed, petition denied) that did not fit our framework. We parsed her co-panelists and found ten: justices Huffman, Haller, O’Rourke, Aaron, Irion, Dato, Do, McConnell, Benke, and Nares.

Analysis

Our data analysis supports several broad conclusions:

- Justice Guerrero showed a high degree of consensus.

- There is nothing striking about Justice Guerrero’s opinions or voting pattern. Instead, her voting and opinion patterns are consistent with each other, and with those of her colleagues.

- Justice Guerrero’s concurrences offer insight into her views on due process and restitution fines, and more generally about her approach to dissent.

Justice Guerrero preferred consensus

Our quantitative analysis shows Justice Guerrero achieving a high degree of unanimity, which is consistent with the Court of Appeal’s consensus rate overall. During her time on the Court of Appeal she either authored or joined the majority opinion in 99.7% of her cases, diverging only three times. She concurred in the result in two such instances, and in the third wrote separately. (The separate opinion was on an issue not yet settled by the California Supreme Court; we discuss this below.)

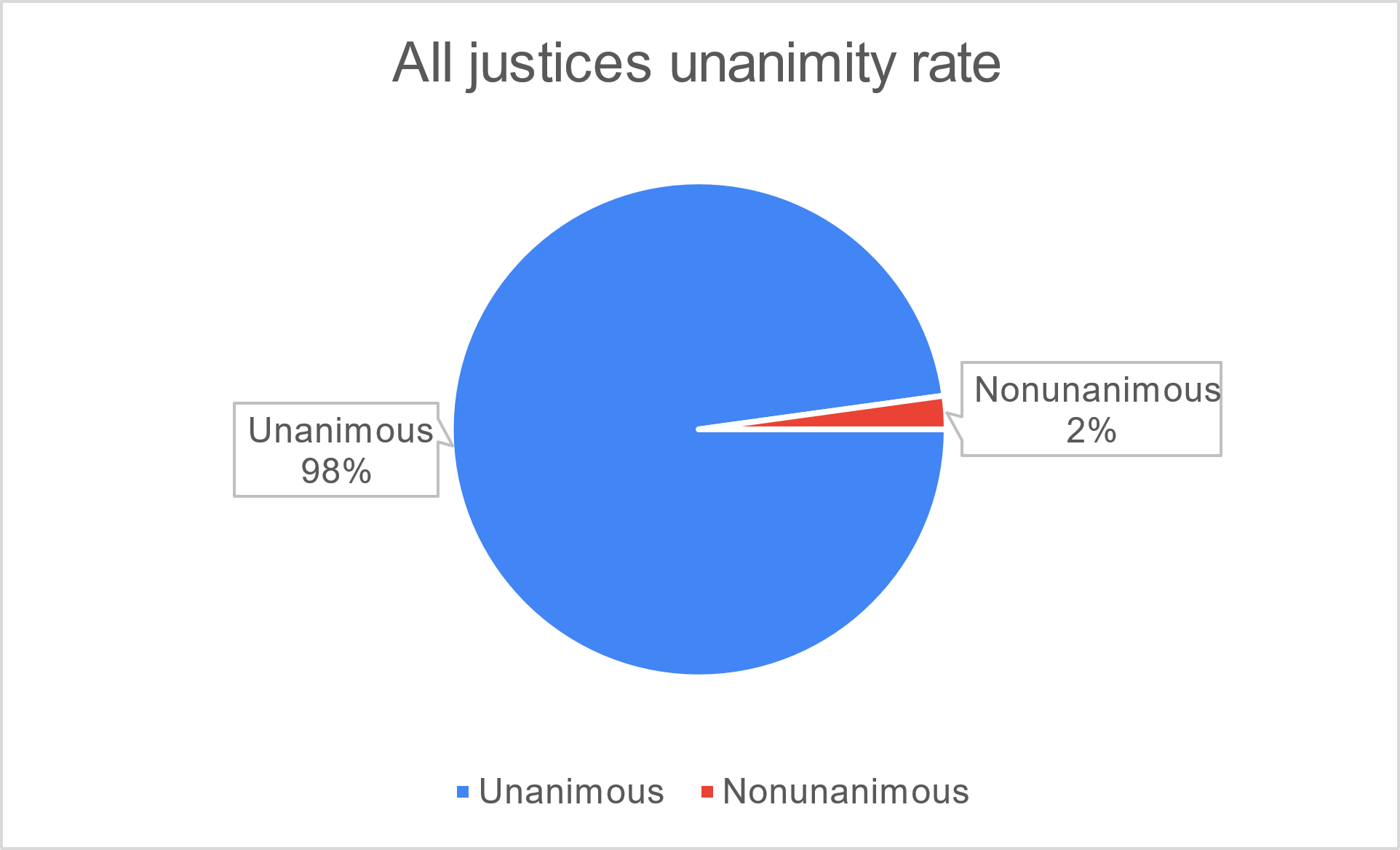

This voting pattern shows Justice Guerrero consistently joining the majority. That accords with her individual behavior on the state high court, where she rarely writes or votes separately on a court that overall has a high unanimity rate. Figure 1 shows the total consensus proportion in all cases Justice Guerrero voted or wrote on while at the Court of Appeal: this includes all nonmajority votes cast by all justices in all her cases. Note that this and all other figures here depict results only from Justice Guerrero’s time and cohort on the Court of Appeal.

Justice Guerrero’s high consensus number sounds remarkable, but in isolation that figure means little without a way to compare it with the unanimity rate of other Court of Appeal justices — and we don’t have one.[1] But we can say that her 99.7% consensus rate is close to the Court of Appeal’s 98% rate, and it would be difficult for the Court of Appeal overall to achieve that figure if there were many justices who frequently dissented.

Another potential comparison is with her current California Supreme Court colleagues.[2] For example, Justice Goodwin Liu has exhibited two clear patterns in his time on California’s high court: in his early years he often wrote separately, and in more recent years he often writes separate statements for denials of review. We could note some broad contrasts here: Justice Liu exhibits distinct behaviors at various times, and both behaviors show dissensus. During Justice Guerrero’s time on the Court of Appeal, by contrast, she behaved consistently over time and showed high rates of consensus while on the court.

Yet there’s limited benefit to such comparisons — the most we would learn is that a particular pair of justices had relatively greater or lesser degrees of consensus. And with such a high unanimity rate, comparing Justice Guerrero to anyone only tells us that the other justice was as agreeable or less agreeable than she was. But we are focused here on Justice Guerrero, and the takeaway here is that her individual 99.7% unanimity rate squares with both the overall consensus performance of her Court of Appeal colleagues (at 98%, see Figure 1), and with the California Supreme Court’s recent unanimity rate.[3]

Justice Guerrero tended to affirm

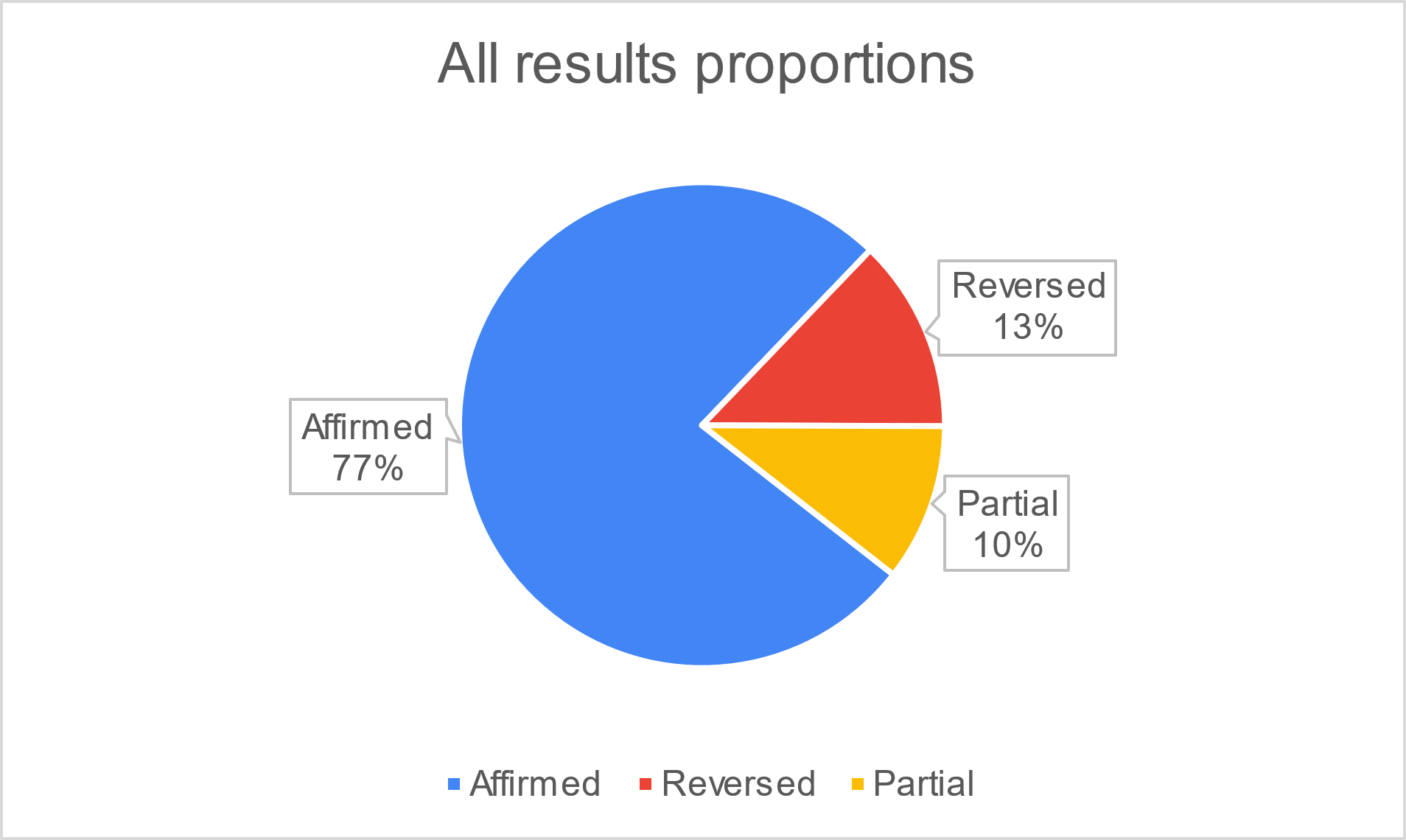

Overall the Court of Appeal generally affirms; for example, in fiscal year 2023 the Court of Appeal affirmed in 77% of appeals resolved by written opinion.[4] The same is true for Justice Guerrero: 77% of her cases were affirmed, consistent with the most recent figure for the Court of Appeal statewide. Figure 2 shows the frequency of each result type across all cases with Justice Guerrero participating. Again, partial is a split result: any judgment reversed in part and affirmed in part.

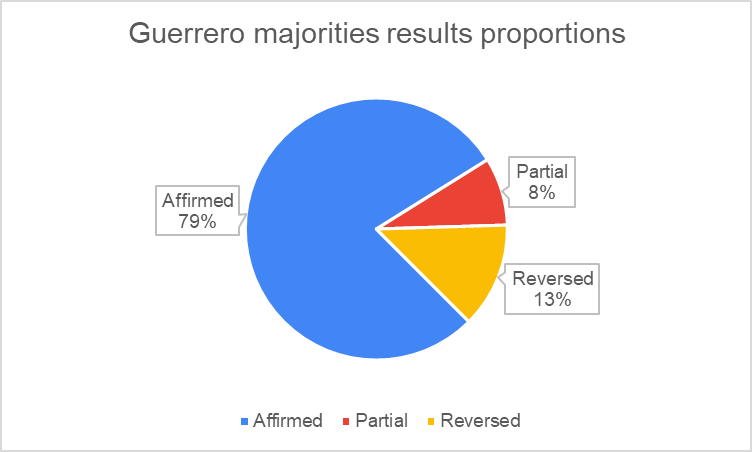

The results are similar if we only examine decisions Justice Guerrero authored. Of these decisions, 79% affirmed the lower court. Figure 3 shows the majority opinions by Justice Guerrero and the proportions of affirmed, reversed, and partial results. This pattern is consistent with deferring to lower court rulings. Such deference should be expected in an appellate system where many presumptions favor the trial court result — and appeals as a matter of right in criminal cases can produce many unsuccessful appellate claims.

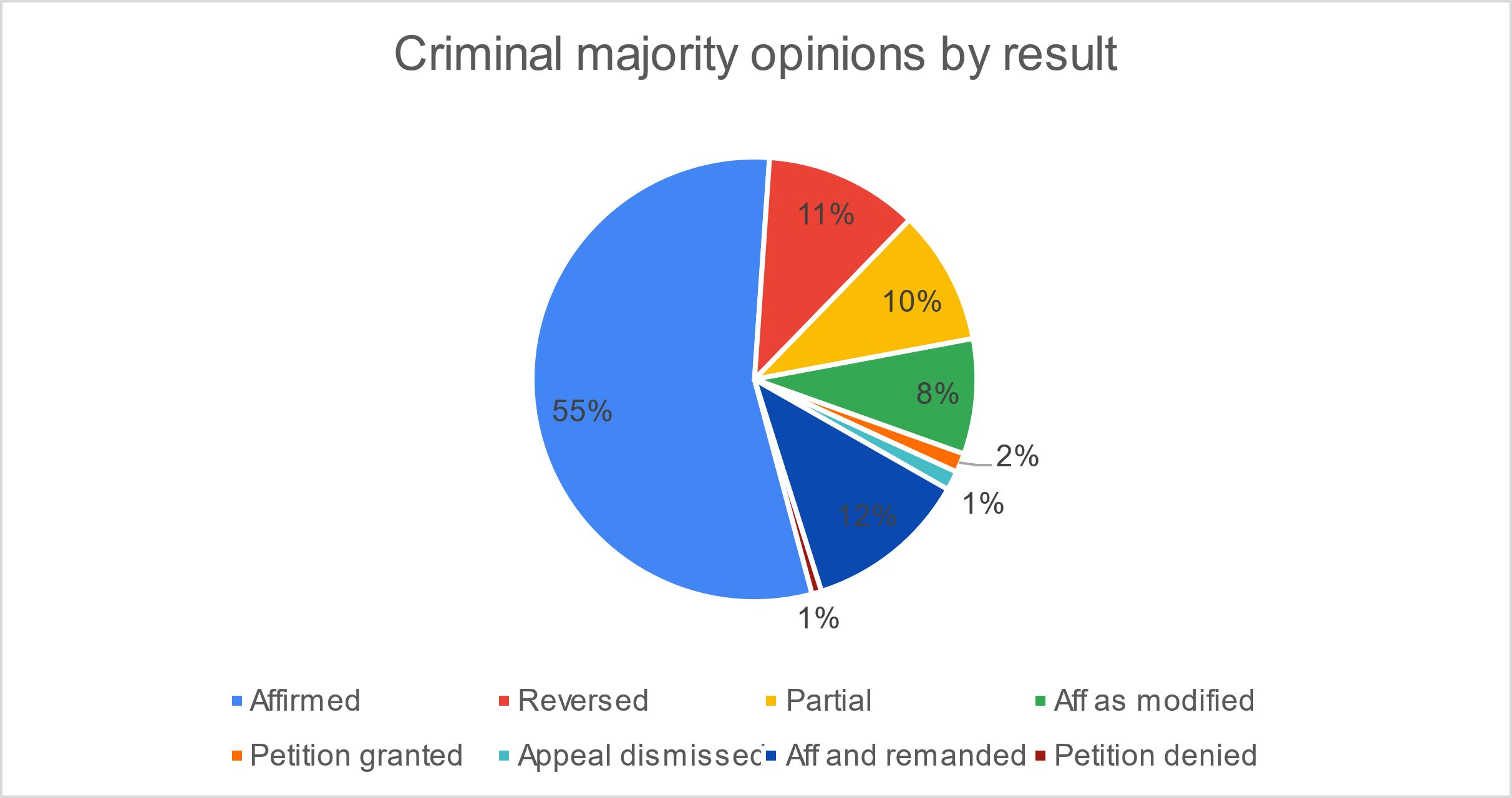

As noted in the methodology section above, we also coded the case results into subcategories to look for any patterns. Those results are shown in Figures 4 and 5. We did see one interesting distinction: Justice Guerrero was more likely to fully affirm civil cases (69%) than she was to fully affirm criminal cases (55%).

Yet that is slightly misleading because Justice Guerrero reversed 13% of civil cases compared to 11% of criminal cases. The main difference is that Justice Guerrero was more likely to affirm and remand a criminal case to a trial court (12%) compared with civil cases (1%). Adding together the affirm and affirm-plus-remand rates produces a total of 70% for civil cases and 67% for criminal cases, showing the remand variable’s significance.

This should be unsurprising for criminal cases given how much change has occurred in criminal law (particularly sentencing) in the past five years. During this dataset’s time window a wave of criminal justice reform measures required the appellate courts to remand cases for resentencing determinations. These reforms either affected criminal sentencing for cases that were not final and pending appeal, or retroactively imposed resentencing measures for final cases with a right to appeal if resentencing was denied.[5] And the California Supreme Court decided lead cases interpreting Propositions 47 and 57 during Justice Guerrero’s first two years on the Court of Appeal.[6] The upshot is that criminal cases are now frequently remanded for basic custody credit calculations or resentencing consideration.

These changes are reflected in Justice Guerrero’s cases, where 12 of her 18 affirming-and-remanding dispositions were for sentence reconsideration. Sentencing is complex and does not apply to civil cases, making a civil case less likely to be remanded with instructions. This can explain the discrepancy between Justice Guerrero’s civil and criminal affirming rates, so it should not be read as evidence of any ideological bias. And as noted above the past five years have seen great upheaval in criminal sentencing law, so looking forward (barring another sea change in criminal law) appellate affirmance rates should increase as this area of the law stabilizes.

Overall, Justice Guerrero’s opinions are typical of any Court of Appeal justice: high consensus, generally affirming the trial court. Her voting pattern, discussed next, shows much the same.

Justice Guerrero’s voting behavior is consistent with her opinions

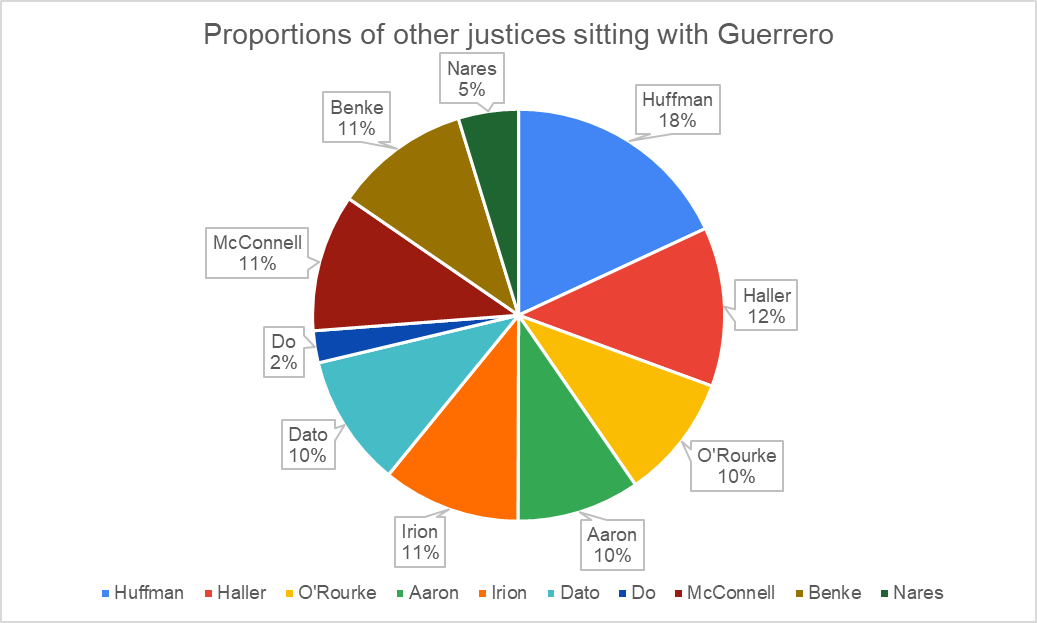

Justice Guerrero’s voting pattern is consistent with her opinion pattern and with voting by her colleagues. A justice can behave differently when in the majority or the minority; for example, even a justice who often votes in the majority might reveal a preference for a colleague or consistently vote against another, and those distinctions might change depending on subject-matter. But that’s not the case here. Justice Guerrero’s panels displayed uniformly high levels of consensus. No single justice emerged as a frequent dissenter. Figure 6 shows how often other justices appeared on panels with Justice Guerrero, regardless of case subject or result.

This shows a rather predictable distribution, except for justices Huffman, Nares, and Do, with Justice Huffman appearing most frequently and Justice Do the least. Those outliers are explained by the calendar: Justice Do was seated in 2021, shortly before Justice Guerrero departed, Justice Huffman is quite senior (appointed in 1988) and was seated throughout Justice Guerrero’s tenure, and Justice Nares only served with Justice Guerrero for about two years before he retired in August 2019.

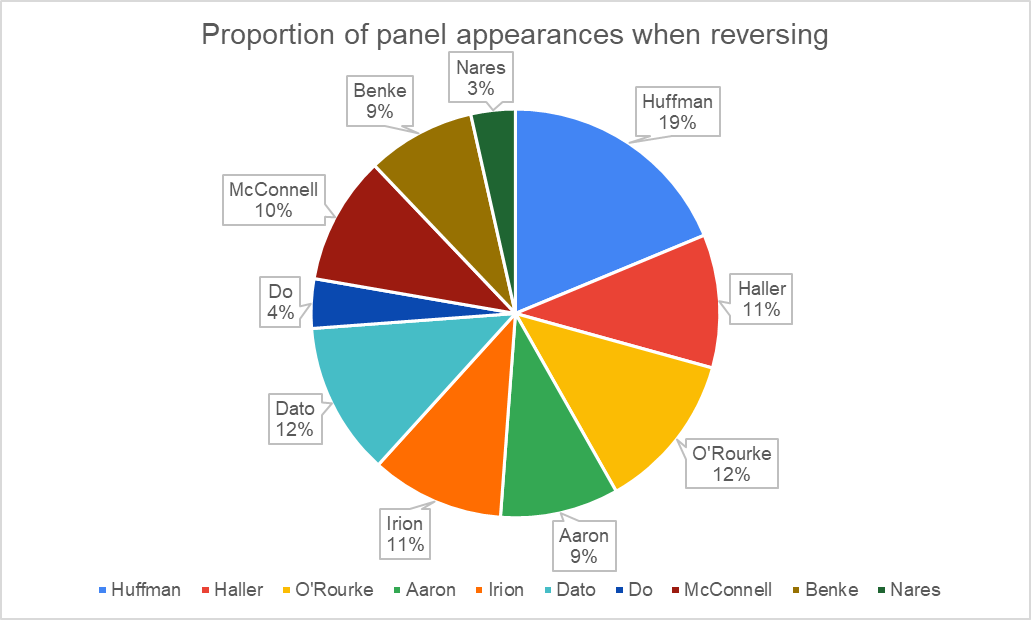

Those proportions are very similar to the proportions depicted in Figure 7 and Figure 8, showing which justices were on the panel with Justice Guerrero when the judgment was for affirmance or reversal. These minor differences in the proportions suggest that the panel membership did not affect the result.

The consistency of these figures shows that who Justice Guerrero sat with does not correlate with case outcome. And it suggests that Justice Guerrero behaved the same regardless of who she sat with.

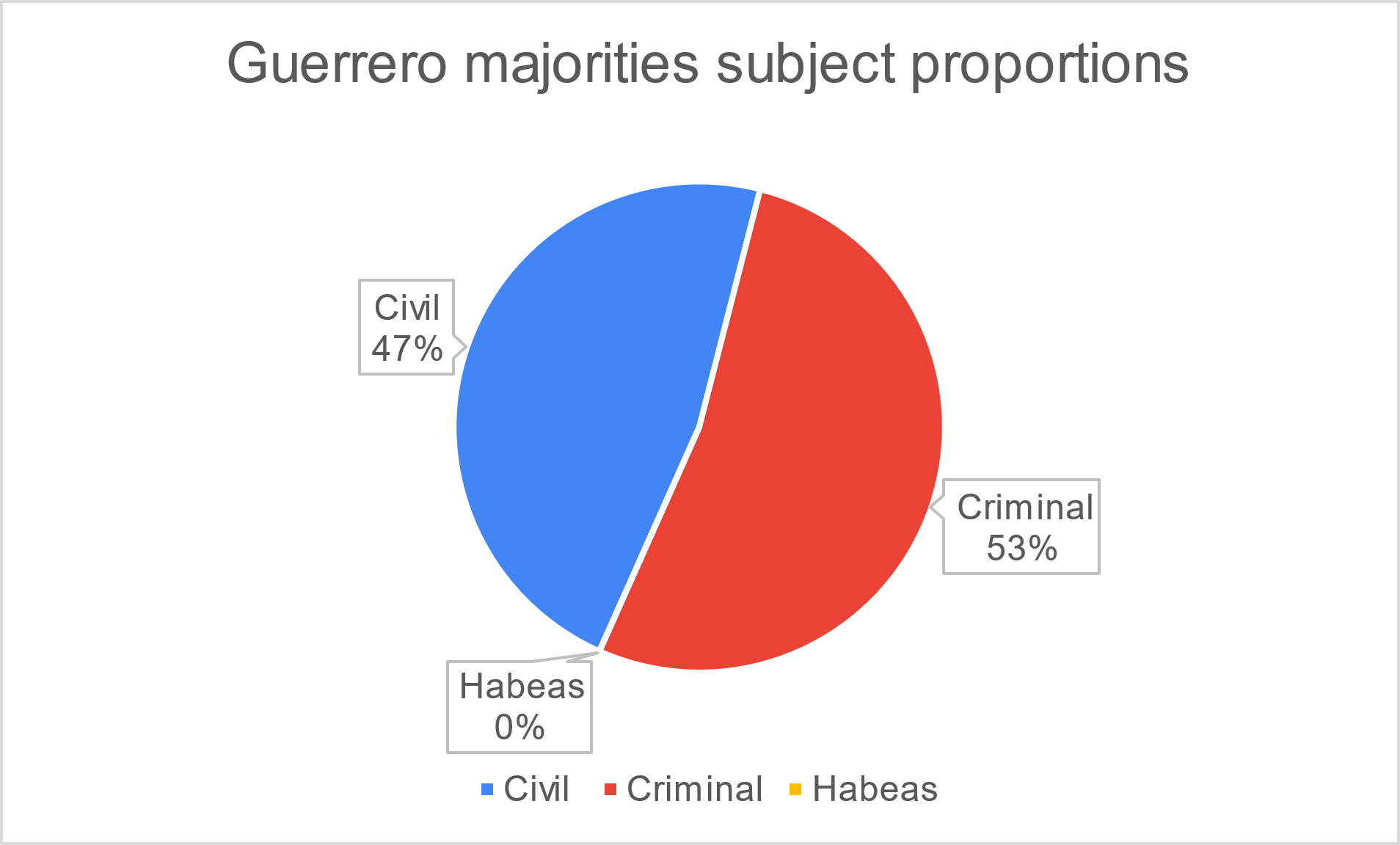

Justice Guerrero fielded a typical distribution of case types

Figure 8 shows that of all cases with Justice Guerrero participating 56% were criminal and 44% were civil. This distribution does not suggest a preference or specialization; the small majority of criminal cases is consistent with the case type balance typical across the Court of Appeal.[7]

Comparing Figure 9 with Figure 10, there is a small three-point difference between the overall proportions and the case type proportions when Justice Guerrero wrote the majority opinion.

This minor variance shows that Justice Guerrero’s cases had no bias favoring a particular subject matter. And these figures, both for all cases with Justice Guerrero and her majorities, are largely consistent with the Fourth District overall. For example, the Fourth District’s cases in fiscal year 2023 were 40.37% civil and 59.62% criminal, and in fiscal year 2022 those figures were 44.09% civil and 55.90% criminal.[8] Justice Guerrero’s case type proportions are quite close to those overall proportions.

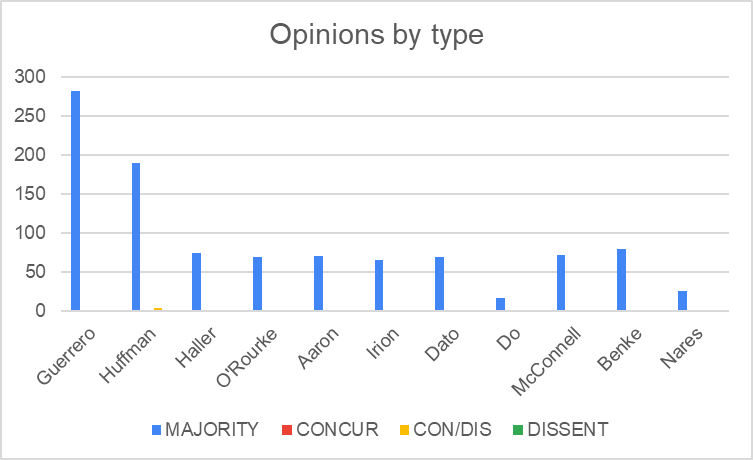

The all-justices overall results show no clear alignments

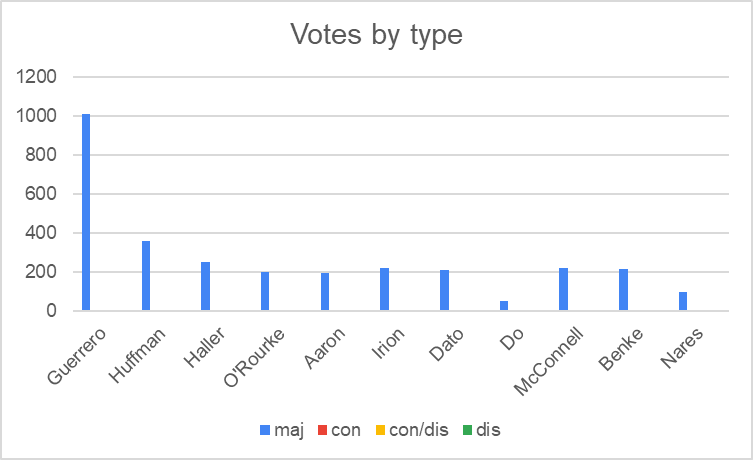

Figures 11 and 12 include all of Justice Guerrero’s opinions and votes, respectively, during this 2017–22 study period, and the votes-and-opinions of the other justices when sitting with her. These figures show the relative occurrence of the four types of opinions and votes in the dataset. They should not be read to suggest that she was the standout leader among her colleagues; the other justices of course sat on other panels, and these figures do not include whatever opinions those justices wrote or votes they cast in those other cases.

These figures show that Justice Guerrero’s votes and opinions were typical of the other justices she sat with: all her panels showed uniformly high degrees of consensus, with no single justice standing out. We were looking here for whether any of the co-panelists showed any non-majority spikes; were that so we would have investigated further to see if similar spikes occurred in that justice’s other panels or if the behavior was unique to sitting with Justice Guerrero. But as you can see that’s not so: none of the co-panelists had enough nonmajority opinions or votes to warrant further investigation.

Instead, Figures 11 and 12 are all blue because there were so few concurrences, con/dis, or dissenting opinions across all justices — so few that those negligible color slivers are too small to see. The only possible standout result is Justice Huffman, who appears as the most frequent co-panelist in these and other figures below. Other than an increase in volume nothing distinguishes those results. Consistent with the figures above, there is no evidence here of any alignment with or against any other justice. Together, Figures 11 and 12 illustrate in single-justice detail how few nonmajority opinions or votes occurred across all justices in the panels Justice Guerrero participated in.

Comparing relative productivity shows no surprises

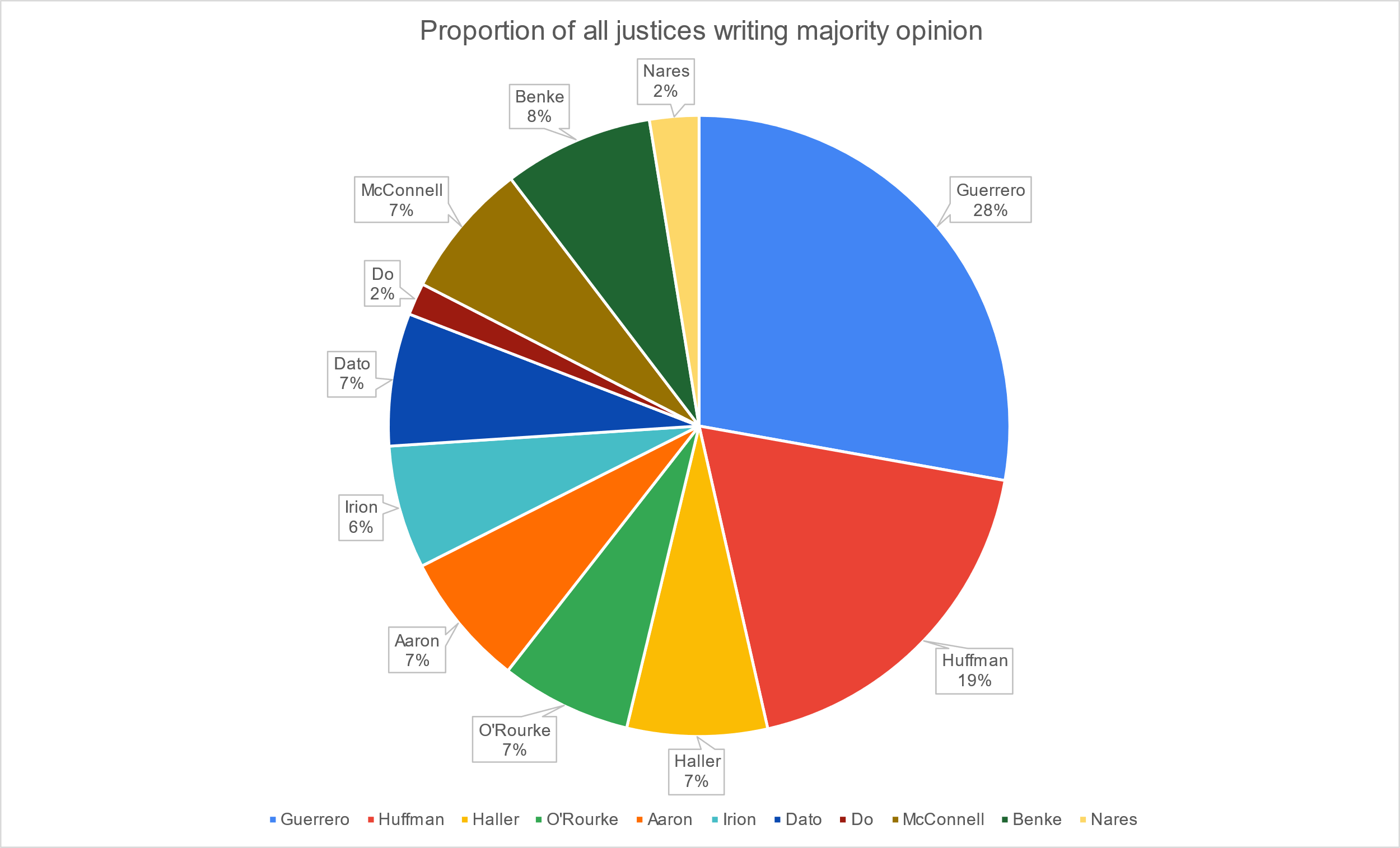

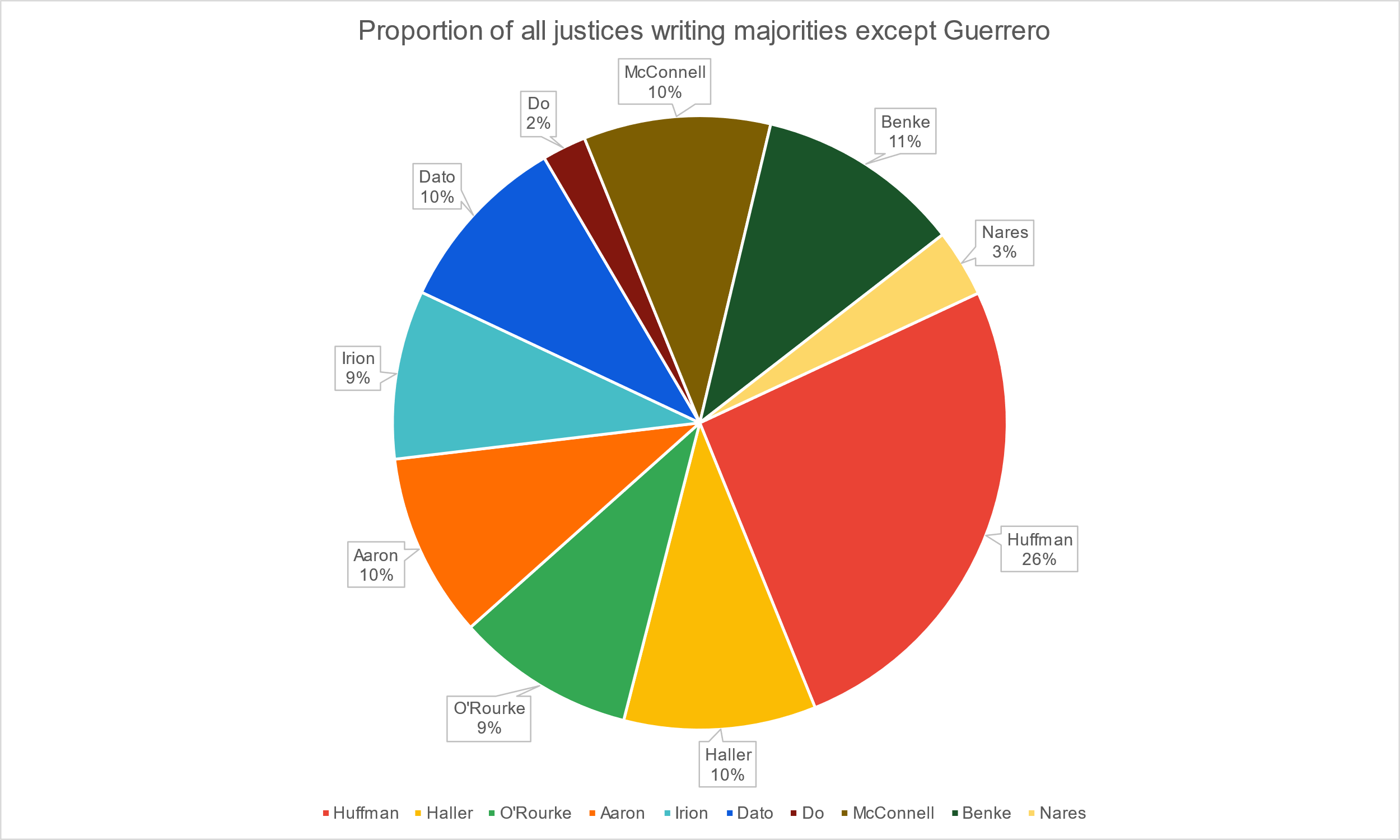

Figure 13 shows who wrote the majority opinion in all cases with Justice Guerrero. Again, this should not be read to suggest that Justice Guerrero was the majority opinion leader because this comparison contains 100% of her majority opinions, but only a fraction of the total majorities written by the other justices in the same time period.

Figure 14 shows who wrote the majority opinion in all of Justice Guerrero’s cases — but excluding her majority opinions to highlight how often the other justices wrote the majority while sitting on a panel with her.

Note that these proportions are consistent with Figure 6 above, showing the overall proportional appearances of the other justices, bearing in mind the same exceptional explanations for justices Huffman, Nares, and Do. As you would expect, here in Figure 14 Justice Huffman and Justice Do wrote the most and least majorities, respectively, because they sat with Justice Guerrero the most and least.

Justice Guerrero’s concurrences have clues about her views on criminal restitution fines

We found only three cases in which Justice Guerrero’s vote or opinion was something other than majority:[9]

- People v. Lopez 2020 WL 5638626

- People v. Stevens 2020 WL 288124

- People v. Scott 2020 WL 64676

Justice Guerrero concurred in the result in Lopez and Stevens and wrote separately to concur in part in Scott. All three cases concerned criminal fines and fees. The concurrences all stem from People v. Dueñas (2019) 30 Cal.App.5th 1157, which held that due process requires trial courts to consider a defendant’s ability to pay before imposing a restitution fine. Dueñas has been criticized — including by Justice Benke, one of Justice Guerrero’s former Fourth District colleagues.[10] In Stevens and Lopez Justice Benke (who wrote the majority in both cases) distinguished Dueñas, with Justice Guerrero concurring only in the result.[11] Although the California Supreme Court decided against depublishing Dueñas, the court later granted review in People v. Kopp to answer the questions Dueñas posed: whether a court considers a defendant’s ability to pay fines and fees before imposing them, and if so, who bears the burden of proof on the defendant’s inability to pay.[12] That case remains pending.[13]

Justice Guerrero’s sole written concurrence showed her restraint on the Court of Appeal. In Scott she wrote separately to argue that certain defendants should be allowed to assert their claims under Dueñas “on remand rather than address the merits” during the initial appeal.[14] Her concurrence argued for giving defendants the burden of proving their inability to pay at resentencing proceedings, and for assessing the ability-to-pay determination based on a defendant’s ability to earn. Justice Guerrero did not otherwise take a position on the merits of Dueñas, deferring instead to the California Supreme Court.

Justice Guerrero’s concurrence in Scott is also consistent with how related issues are treated in Justice Guerrero’s majority opinions. For example, People v. Gonzales held that defendants who did not object to the restitution fee before the appeal forfeit their right to challenge the fine under Dueñas.[15] And People v. Garcia held that even if the California Supreme Court upheld Dueñas, the decision would only apply to non-punitive fines, with analysis of defendants’ ability to pay punitive fines reviewed under an Eighth Amendment analysis.[16] Justice Guerrero’s concurrence in Scott shows both her restraint and her consistency on the Court of Appeal.

Not all of Justice Guerrero’s colleagues shared her restraint in their concurrences. For example, Justice Huffman’s concurrence in People v. Armijo shared his more critical view of Dueñas.[17] Justice Huffman argued that Dueñas should be limited because the case was based on “extreme facts.”[18] Similarly, Justice Benke wrote in People v. Kopp that parts of the Dueñas holding were “erroneous.”[19] And in People v. Gutierrez she again wrote separately to express her “disagreement” with Dueñas.[20] In contrast, Justice Guerrero took a more neutral stance. Her approach emphasizes patience and restraint by waiting for guidance.

Justice Guerrero’s individual approach to Dueñas is the lone example of her departing from a majority view, and it highlights her composure even in disagreement. She expressed a separate view just once, despite having multiple looks at the issue.[21] Rather than staking a claim on how Dueñas should ultimately be decided, Justice Guerrero identified the issue and then waited for the California Supreme Court to resolve the matter. That showed restraint.

Conclusion

Justice Guerrero’s tenure on the Court of Appeal was notable for its high degree of unanimity, which identifies her as a solid majoritarian. Her caseload reflected the general appellate docket of civil and criminal cases, she affirmed or reversed in typical proportion, and none of the external factors we evaluated here seemed to affect her behavior. In the one area we found divergence, she stated her differing view and otherwise showed restraint when a different justice might have made a cause of it. It will be interesting to see whether and how this behavior pattern carries into her new chief justice role; note, for example, that in her first full year in that position the court marked its highest unanimity rate in recent history at 94.23%.[22] Overall, our analysis describes a solid appellate justice with strong majoritarian characteristics who is restrained in the rare instance of disagreement.

—o0o—

Ben Pearce and Lauren Jozefov are research fellows at the California Constitution Center.

Most statistical studies of appellate body agreement focus on nonunanimous decisions. See, e.g., Gergen, Carrillo, Chen, Quinn, Partisan Voting on the California Supreme Court (2020) 93 So.Cal.L.Rev. 763; Goldman, Voting Behavior on the United States Courts of Appeals Revisited (1975) 69 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 491, 491–506. ↑

This is a bit apples-and-oranges, since the roles of an intermediate appellate court and the high court are distinct, but the high-level contrast point remains fair. For example, automatic appeals in capital cases bypass the Court of Appeal. That does not prevent a justice — of either court — from exhibiting a distinct voting or opinion pattern. So that does not undermine our high-level comparison of the distinct behavior patterns of these two bench officers. ↑

California Constitution Center, SCOCA year in review 2023, SCOCAblog January 8, 2024 (in her first full year as chief justice the court marked its highest unanimity rate in recent history at 94.23%). ↑

California Judicial Council, 2024 Court Statistics Report at 34 (Courts of Appeal, Appeals Terminated by Written Opinion, Figure 22: Total Appeals FY23). ↑

See, e.g., SB 1437, SB 1393, SB 775, SB 620, SB 136, and SB 567. ↑

See, e.g., People v. Lara (2010) 48 Cal.4th 216, People v. Buycks (2018) 5 Cal.5th 857, People v. Romanowski (2017) 2 Cal.5th 903, and People v. Frahs (2020) 9 Cal.5th 618 (all concerning the mental health diversion law and whether it applied retroactively to nonfinal cases). ↑

Overall the Court of Appeal had 58% criminal case dispositions by opinion in 2023 and 62% in 2022. Justice Guerrero’s Fourth District, Division 1 had 60% criminal case dispositions by opinion in 2023 and 53% in 2022. California Judicial Council 2024 Court Statistics Report at 40. ↑

Using data reported in California Judicial Council 2024 Court Statistics Report at 40. ↑

In People v. Perez (2018) 19 Cal.App.5th 818, Westlaw’s formatting inaccurately shows Justice Guerrero as concurring. We counted this as a majority vote because the original opinion shows her with Justice Haller in a “we concur” signature block, which indicates full endorsement of the opinion. ↑

See, e.g., People v. Kopp (2019) 38 Cal.App.5th 47, 98 (Benke, J., concurring in part) (“I respectively believe Dueñas erroneously invoked a due process and equal protection analysis”); People v. Gutierrez (2019) 35 Cal.App.5th 1027, 1034 (Benke, J., concurring in part) (“I write to express my disagreement with Dueñas, which I believe misapplies California’s statutory law and erroneously selects a general due process and equal protection theory as the basis for its decision”). ↑

People v. Lopez 2020 WL 5638626 at *2; People v. Stevens 2020 WL 288124 at *3. ↑

People v. Dueñas, depublication request denied 03/27/2019 S254210; People v. Kopp (2019) 38 Cal.App.5th 47 (review granted November 13, 2019 S257844). ↑

See, e.g., People v. Mahmood 2024 WL 4290661 at *3 (“Our Supreme Court is currently considering the issues raised in Dueñas”). ↑

People v. Scott 2020 WL 64676 at *16 (Guerrero, J., concurring in part). ↑

People v. Kopp (2019) 38 Cal.App.5th 47, 98. ↑

People v. Gutierrez (2019) 35 Cal.App.5th 1027, 1034 (Benke, J., concurring in part). ↑

Dueñas is cited in 55 cases with Justice Guerrero presiding. See, e.g., People v. Cox 2021 WL 628530 at *5 (“We express no opinion on the merits of Cox’s objection to the restitution fine and fees”). ↑

California Constitution Center, SCOCA year in review 2023, SCOCAblog January 8, 2024. ↑