SCOCA year in review 2023

Overview

Our word to describe the California Supreme Court in 2023 is coalescence. It makes no difference how long a justice has served, who appointed the justice, what political party they vote for, or what kind of toast they like — the metrics we track for this court all show collapsing trends with few divergences. The three-way split between the appointing governor blocs remains: three Browns (Liu, Kruger, Groban), three Newsoms (Guerrero, Jenkins, Evans), and one Schwarzenegger (Corrigan). But those looking for polarized voting blocs or even a lone dissenter will be disappointed: this court most often operates as a cohesive unit.

The practical developments this year that could potentially affect that macro-level perspective were few and without apparent effect on the larger trends. The court added just one new member in 2023 (Justice Kelli Evans), and transitioned chief justices from Cantil-Sakauye to Guerrero. No justices stood for retention election. There was no budget crisis this year, although one seems likely in 2024. And rather than marking an inflection point for the court’s opinion output, this year’s opinion output seems to confirm a trend of annual opinion tallies in the 50s — which means we (again) must consider the quality-versus-quantity debate. In this iteration we review empirical scholarship on state high courts, which suggests that appellate courts should be assessed on the quality of opinions not their quantity. That perspective confirms our previous view that there is little reason for concern about the court’s health.

Analysis

Opinion metrics

The court issued 52 merits opinions in 2023, up one from the historic low of 51 opinions in 2022. The court’s opinion output has stabilized, settling into the 50–55 range three years in a row, indicating stasis rather than variability or a developing trend. This further suggests that near-term opinion output may remain in this range absent some institutional change. (See this article for a detailed discussion of our thoughts on why the court’s annual opinion output has declined to this level.)

As always, our figures may vary slightly from other sources because we use the calendar year. The Judicial Council’s annual Court Statistics Report follows a fiscal year schedule, and the court issues its own year-in-review report based on a September-to-August year. The court’s most recent report counts 55 opinions from September 1, 2022 to August 31, 2023; the Judicial Council figures for the most recent fiscal year will not be available until summer 2024.

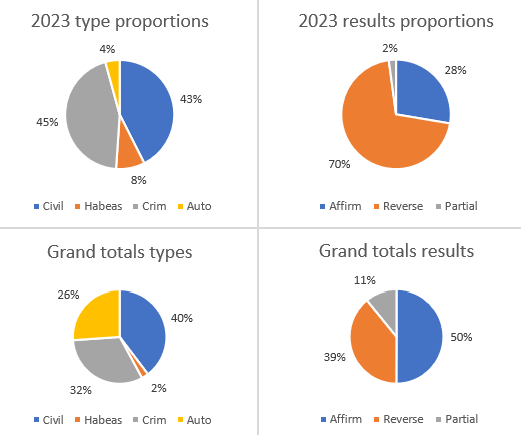

We compared the case types and results for this year with the same calculations for the most recent 12 years in our recent “Appellate rules of thumb” article.[1] This year’s proportions diverge from the whole-period results for both case types and results. Civil decisions in 2023 were roughly the same as the whole-period average, but with only two automatic appeals this year the general criminal slice is much larger. (Four habeas petitions is not an unusual yearly number; that slice looks much larger in 2023 because its denominator is the relatively small number of cases decided this year.) The court reversed far more cases this year than the 12-year average, affirmed fewer than the long-term average, and issued fewer partial decisions.

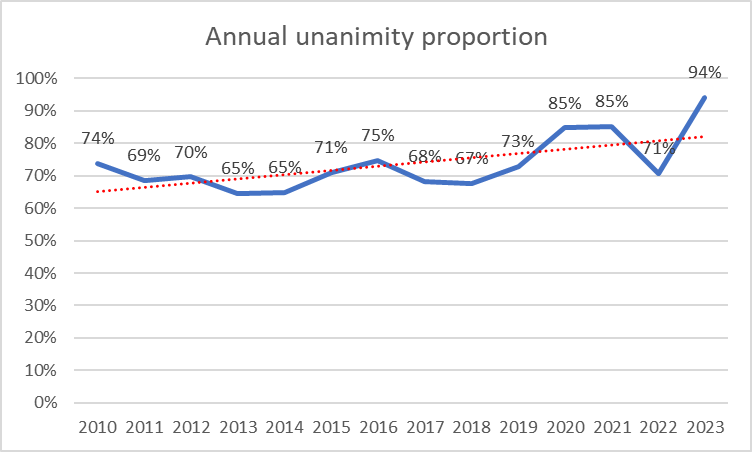

Unanimity was rather surprising this year. We expected the high-unanimity trend to either maintain or perhaps moderately increase, but instead the court marked the highest unanimity rate in its recent history at 94.23%. This is a sharp upward deviation from both the previous year and from the gradually increasing recent trend.

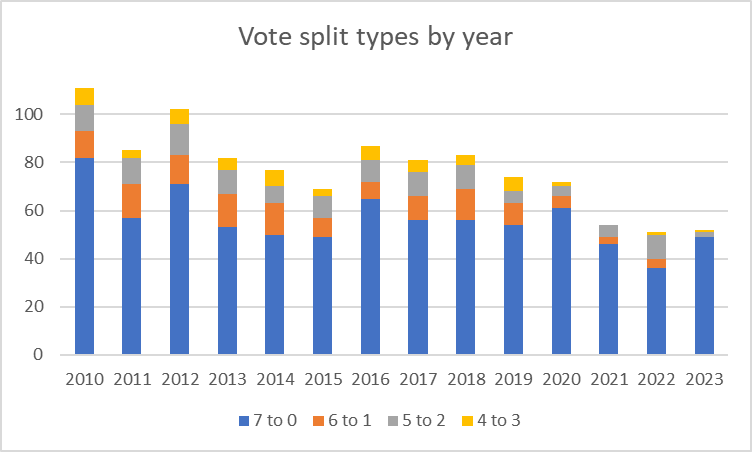

Indeed, this year’s 94% result may be an all-time record for highest unanimity percentage; the next closest result in our data is 89.18% unanimity in 1918. This is the clearest expression of the coalescence we see on the court, and it is supported by other metrics. For example, vote splits are another way of measuring how divided or united the court might be. The next figure shows that proportionally all vote splits decline over time.

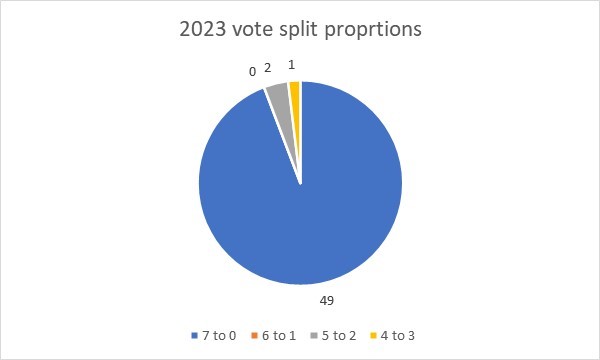

And this next figure shows that nonunanimous votes are a negligible data slice this year, with only three nonunanimous opinions: two 5–2 splits and one 4–3 split. Justices Liu, Kruger, Groban, and Evans were the only justices who either cast non-majority votes or wrote separately for the year.[2] The only two cases with either dissents or concurring/dissenting votes or opinions (People v. Braden[3] and People v. Brown[4]) both featured justices Liu and Evans in the minority, with those two justices also signing Justice Groban’s separate opinion in People v. Brown. And Justice Evans signed Justice Liu’s separate opinions in People v. Schuller[5] and People v. Mumin.[6] Let’s see if the apparent Liu–Evans affinity continues into 2024.

All these views suggest that the court is coalescing into a unified body that largely marches in lockstep. It would be a marvel if the court achieved even greater unanimity than this.

The court’s high unanimity rate can be attributed to its collaborative decision-making process. Each case is assigned to a justice when review is granted; the assigned justice is responsible for circulating a calendar memorandum that analyzes the issue presented and proposes a solution.[7] Each justice, in turn, distributes a preliminary response to the calendar memo. Although preliminary responses vary, “[r]arely does a calendar memo emerge from the gauntlet of preliminary responses unscathed.”[8] The justices deliberate immediately following oral argument and then circulate draft opinions.[9] The culture of the California Supreme Court places a “high premium on collegiality and unanimity” and “the justice authoring a majority opinion will typically seek to address and accommodate . . . the concerns of wavering colleagues in order to secure a fifth, sixth, or even seventh vote.”[10] Of course, the court’s unanimity rate has not always been so high as it is now, despite the fact that this opinion-writing process has persisted for decades.[11] We attempt to explain this in the next section.

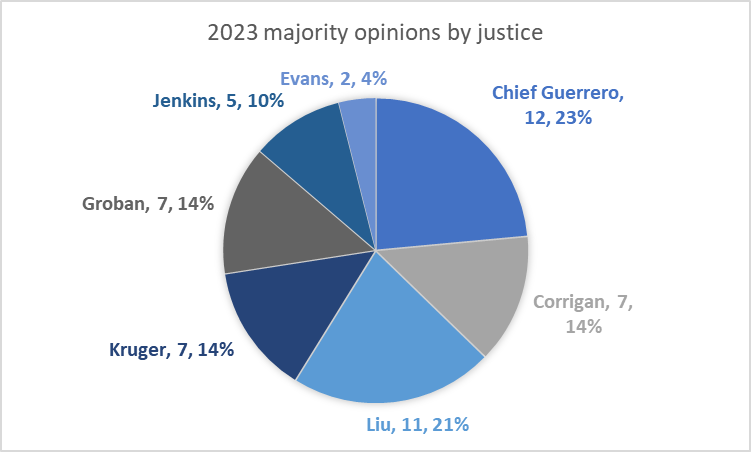

Turning to the individual justices, nothing about their current-year performance detracts from our coalescence conclusion. The justices are rather evenly distributed in authoring majority opinions, with no clear leader identifiable. The fact that Justice Evans wrote just two majorities is expected given that this is her first year on the court, and a partial year at that.

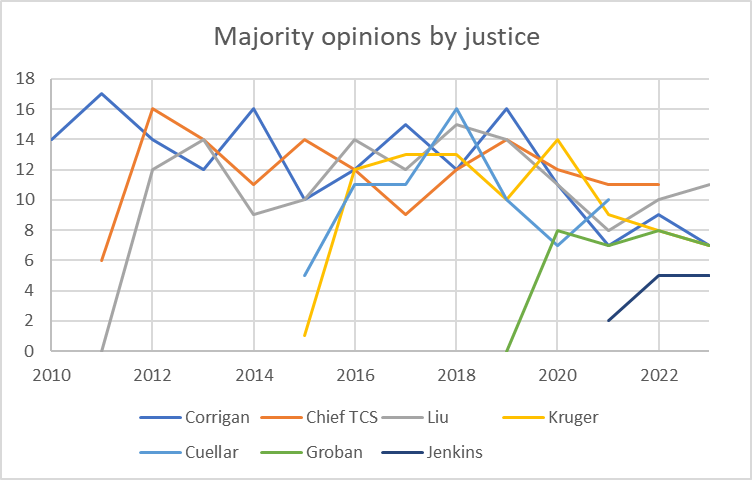

Tracking the individual justices shows that (after their first year) all the justices perform consistently. With some natural year-to-year variation in individual output, the justices remain close to each other as the court’s overall output changes. Over time, no individual justice stands out a consistent leader in majority opinion output. We can say that Justice Corrigan has highest average yearly majorities at 12.29, narrowly beating former Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye at 11.83; of the current members Justice Liu is the closest competitor at 10.77. But these are small differences, and the justices are otherwise rather tightly grouped year to year.

Chief Justice Guerrero and Justice Evans are not included in this figure due to their short service to date. If they were included both would have initial ramp-up lines similar to the other justices depicted and would appear as outliers like Justice Jenkins (who joined the court in 2022). As an associate justice in her first year Chief Justice Guerrero authored no opinions, and then authored a full complement of 12 majorities in 2023. And Justice Evans authored two majorities this year; if she performs consistently with her colleagues one expects somewhere around 10 majorities from her in 2024. Thus, we expect that both the Chief Justice and Justice Evans will by next year exhibit the same pattern depicted here for new justices: a low-output first year after which they join the pack. This supports both our coalescence theme and our previous point about a new justice causing a temporary slowdown in that chamber’s opinion output.

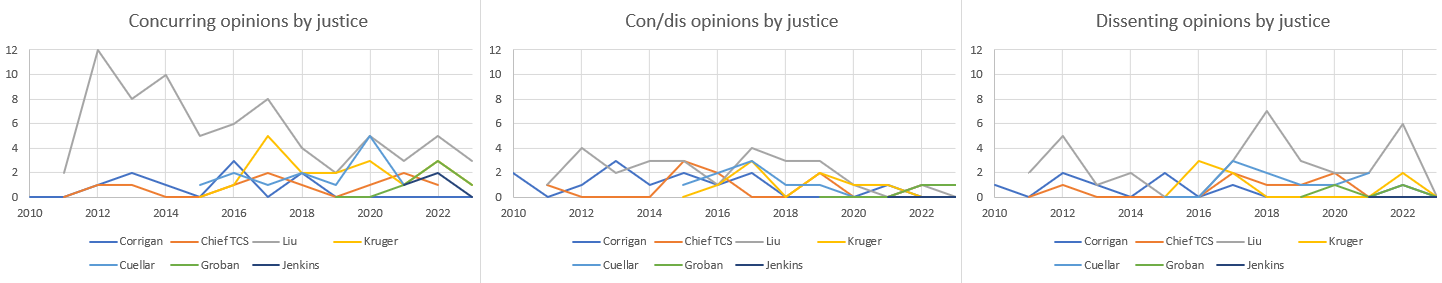

The separate opinion output by individual justices further reinforces our coalescence theme. Over time, all separate opinions by all justices fall, and every justice now writes just a few separate opinions each year — in 2023 there were just seven total separate opinions.

As these figures show, even Justice Liu has drawn largely even with his colleagues, overall producing far fewer opinions than he previously did, and now he writes separately in rough proportion to all the other justices.

The upshot is that all these views on the court’s performance since 2010 (unanimity, vote splits, majority authorship, separate opinions) support the same conclusion: the court’s justices have coalesced into a unified group that rarely sees even small differences of opinion. With the court so much of one mind, and with annual opinion numbers remaining low, we thought we should revisit the quality-or-quantity question.

Fewer opinions, but better

To further assess the quality-or-quantity question we reviewed quantitative scholarship on state high courts, which generally concludes that such courts “should not be evaluated according to the quantity of opinions produced, but according to the quality of opinions produced.”[12] This means that state high courts should focus on carefully shaping statewide law by writing fewer and better opinions.[13] That conclusion flows from the nature of state high courts — particularly those with intermediate appellate courts like California, which sit to provide broad clarity in the law rather than to correct errors.[14] That indeed is how the California Supreme Court characterizes its primary role: “The Supreme Court may order review of a Court of Appeal decision . . . [w]hen necessary to secure uniformity of decision or to settle an important question of law.”[15]

One expects such a court, with nearly full discretionary control over its non-capital docket, will choose carefully among petitions for review rather than swinging at every pitch. And a court with fewer separate opinions arguably better serves its primary function of producing clear statements of law, because more separate statements qualifying the majority opinion obscure its reasoning and make it harder to determine what the law is going forward.[16] In short, the court’s key role as final arbiter of California law argues for care in deciding cases, with clear consensus decisions, rather than taking that power as a roving writ to chase issues that can only be decided with narrow majorities in fragmented decisions. The studies we reviewed largely support that view for a high court structured like California’s — with the caveat that comparisons between the 50 state high courts are inexact, because those courts exhibit wide variation in their structure and environment, and consequently they present a range of annual opinion outputs.

Yet despite those differences studies have found that state high courts produce opinions in a consistent and narrow range of values. For example, one study of 16 state high courts between 1870 and 1970 found that some wrote upwards of 500 opinions per year, while others wrote fewer than 100.[17] Another study found that although the annual output fluctuated over time (from population changes and other factors) it stayed within a rather small range: from an average of 131 opinions per court in 1870, to a high point of 291 per state in 1915, decreasing into the early 1970s.[18] The authors concluded that “the consequences of writing a relatively high number of opinions are not positive, as doing so results . . . an overall lower quality of output than these state courts had produced in earlier periods,” which “seriously impaired” the capacity of those courts to serve their function of articulating legal policy for the state.[19]

Scholars and justices have explained the consistency of the opinion ceiling by pointing to practical restrictions. State high court justices might have only 200 or so working days a year, so deciding 100 cases per year would require the justices to issue an opinion every other day.[20] Consequently, if the number of justices on a state high court remains constant, then the number of opinions that they can thoughtfully author has an upper limit.[21] By one generous estimate an appellate justice could in theory author 100 opinions per year.[22] Yet other estimates are far lower: “no appellate judge, however competent, can write more than 35, or conceivably 40, full-scale publishable opinions in a year.”[23]

Empirical results support the more conservative estimate, with a study of recent decades finding a narrow range of state high court decisions: an overall average of 190 opinions per year, with seven-judge courts (like California’s) issuing an average of 183.9 opinions per year.[24] Seven justices producing 182 annual decisions is about 26 opinions each. That’s about double what the California Supreme Court’s per-justice output has been in the past three years. But even when its output was around 100 annual decisions (in 1998–2000) California’s high court ranked 16th in one comparison of productivity results by state high courts, ranked by total number of published opinions per judge-year.[25] So although it’s true that California’s overall and per-justice opinion output has fallen, that’s not necessarily bad, and in any event the state has historically not been an output leader.

That history suggests that something structural is influential here, in particular a structural feature that has been in place for many years. We suspect that California’s judicial-selection system may have a significant effect on the court’s consensus, the number of annual opinions, and the quality of those opinions. Since 1934 California’s judicial selection system has followed the Commonwealth Club Plan.[26] While many states employ either an exclusively elected system or an exclusively appointed model, California combines elements of both systems, with initial gubernatorial appointments for all bench officers, followed by either contestable elections for trial judges or uncontested retention elections for appellate justices. Periodic proposals to change this mashup system, as recent as a legislative proposal in 2000, have never taken flight.[27] Because California’s hybrid appointment/retention system is unique, it is difficult to compare with the empirical results for pure election or appointment systems.[28] But a few comparisons are possible, and illuminating.

Some scholarship suggests that the hybrid California model exhibits at least one beneficial characteristic of an appointment system: higher quality opinions. Frequency of citation is one way to measure opinion quality, with higher citation numbers suggesting greater quality.[29] One study showed that appointed justices generally write higher quality opinions, as measured through citations — perhaps because appointed justices are more concerned with building their personal body of precedent compared with the more public-facing concerns of elected justices.[30] In a study of followed rates for California Supreme Court opinions, the authors found that (consistent with previous studies) the California Supreme Court “has long been, and continues to be, the most ‘followed’ state supreme court.”[31] With California “far ahead of the other states” in citations, its opinions likely are of higher quality.[32]

Other studies similarly suggest California’s high court exhibits positive attributes. Its high consensus rate is an inherent good: “Consensus signals certainty in the law, legitimizing a decision as the other branches of government, and the public see the court speaking with a singular voice.”[33] Shorter opinions are faster reads, and studies of the U.S. Supreme Court show that unanimous decisions tend to be shorter.[34] Consequently, by producing fewer but higher-quality (and perhaps shorter) opinions the California Supreme Court is behaving much as expected.

There are downsides for high-majority courts, which can be avoided by courts that decide cases with small or bare majorities. One study found that the clearest (in the sense of being easiest to understand) majority opinions come from minimum-winning coalitions.[35] And elected courts have both higher dissent rates and higher degrees of differing perspectives among the justices.[36] Having the benefit of those diverse voices in the books has its advantages, as suggested by studies that show elected justices having higher risk-taking propensities.[37] Today’s lone dissenting opinion might be tomorrow’s wisdom.[38] California’s high-consensus court will miss out on these positives.

The upshot is that there are tradeoffs, and California’s judicial selection system’s design incorporates compromises with consequences. Having all-elected judges would have some benefits and disadvantages, just as an all-appointed judiciary would have an inverse set of advantages and downsides. By blending the two models California’s hybrid system assumes some of both sets of upsides and problems. Rather than using opinions primarily as signals to external actors, justices on retention-election courts like California’s are “more focused on internal conditions and constraints in crafting opinions”[39] and more concerned with creating lasting precedent.[40] Thus, California’s judicial selection is biased in favor of greater consensus, fewer and shorter opinions, and greater focus on building doctrine.[41] That arguably favors quality over quantity, which in turn is arguably encouraging the court’s high-consensus and low-output performance. All things considered, “a strong case can be made that California has the best high court.”[42] Even with its inherent compromises, this literature review suggests that California’s high court is performing much as its design would cause it to, and that the results we see have positive features.

This literature review also validates our previous point that the quality-versus-quantity question can be a false choice because, given the inherent tradeoffs, it is largely a normative matter of perspective. Elected justices produce fewer unanimous decisions and more separate written opinions.[43] You might prefer that. But nonunanimous opinions are generally longer, and longer opinions are not inherently of a higher quality.[44] Nor are more opinions necessarily better. And fewer unanimous decisions suggests that a court has durable partisan divisions among the justices, which is not desirable.[45] Again, the competing imperatives here cannot be simultaneously reconciled, even in a hybrid system like California’s.

Of course, the counterpoint is that this current state of affairs (low output with high consensus) has not always existed. The year is always 365 days long, so even if the court’s justices only have about 200 working days a year, how did the court issue hundreds of decisions annually in the past? If selection method alone drove output and consensus those metrics would look roughly the same every year since the Commonwealth Club Plan was adopted in 1934. Indeed, our own data show that the court’s current high-consensus low-output mode is unique in the court’s history. And the current high unanimity rate is at odds with research finding that greater discretionary control over a court’s docket (which the California Supreme Court mostly has) decreases the likelihood of unanimity and increases the likelihood of separate written opinions.[46]

We only argue here that the selection system is a factor, not destiny. We suspect that the court’s design features exerted a gradual effect over time, which explains why the trends for unanimity and output rise or fall slowly but consistently. The parts of the whole tell distinct stories, and support this view. It’s true that the low-output factor is novel, but that likely reflects a long-term trend of the court’s annual opinion numbers gradually falling from hundreds of annual decisions in the early 1900s to about 100 opinions or fewer from 1995 onward. The far higher annual opinion numbers in the early 1900s are easily explained by the court’s use of departments and commissioners. And the current high unanimity rate has been rising since around 1990, reclaiming a high-water mark that resembles the early 1900s.[47] The trend we identify above of few-and-declining separate opinions is consistent with California’s uncontested appellate retention elections, as researchers have proved that elected justices write more separate opinions than appointed justices.[48] The judicial selection process alone cannot explain these trends, but the studies described above suggest that the very fact that those trends exist and have their respective vectors is at least partly due to the selection system’s influence.[49] Thus, we can conclude that our judicial selection system has consequences, and our high court’s current performance must partly flow from that system.

Even the oft-made counterpoint about groupthink is, we think, at least partially addressed by California’s selection system. An obvious potential explanation for the court’s current high consensus rate is the fact that six of the seven justices were appointed by Democratic governors, with Justice Corrigan the lone appointee by a Republican governor. But if partisan affiliation drove justice voting then Justice Corrigan should be a consistent lone dissenter, which is not so — instead, she has the strongest case for majority leader. And if Democratic politics in Sacramento are any indication the party is hardly characterized by uniformity of thought.[50] Unlike in a legislature, the work of appellate courts does not reinforce partisan affiliation, especially courts with uncontested retention elections like California’s.[51] Instead, the selection process either enhances or inhibits the chances of partisan behavior. The lifetime tenure of federal high court justices makes the confirmation hearing all-or-nothing, with modern confirmations heavily dependent on political party support, which naturally selects for doctrinal true believers. By contrast California’s nonpartisan process, with an apolitical vetting-and-confirmation process by the bar and a commission, instead encourages governors to nominate candidates with broad appeal rather than ideological bona fides.

In sum, rather than California Supreme Court justices behaving similarly because they were appointed by members of the same party, their behavioral similarities more likely reflect the broader legal community that endorsed them. Add the fact that empirical studies show that in general courts with retention elections are significantly more likely to reach unanimous decisions than courts with partisan or nonpartisan elections.[52] Those factors may provide much of the explanation for the high consensus rate the California Supreme Court is achieving.

Conclusion

The likelihood of seat changes in 2024 is low, given that no justices will be on this year’s ballot for retention. Four seats were up for retention election in November 2022:

- Justice Groban was retained to fill the remainder of retired Justice Werdegar’s term. She was retained by the voters in November 2014 for a 12-year term that ends on January 3, 2027, so Justice Groban will appear on the November 2026 ballot for a new full term.

- Justices Liu and Jenkins secured new 12-year terms on the court and will not be on the ballot again until November 2034.

- Associate Justice Patricia Guerrero would have been up for retention election on November 8, 2022, but after her appointment and confirmation she replaced Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye on the ballot for retention to a full term as chief justice.[53] She also will next appear on the ballot in November 2034.

Justice Evans will be on the ballot for retention in the next gubernatorial election in November 2026. Justices Corrigan and Kruger will both next be on the ballot in November 2030.

Changes in the court’s membership in the past decade have coincided with observable trends continuing; this suggests that rather than changing the court’s direction the new members are contributing to existing trends. This also supports previous predictions that new appointments to the court are unlikely to substantially change the court’s dynamics between now and the next open gubernatorial election in 2026. This year we will look to how the new chief justice begins to make her mark on the court and the judiciary, and be alert for any signs of change from the court’s now-well-established trends.

—o0o—

Senior research fellows Stephen M. Duvernay, David A. Belcher, and Michael J. Belcher contributed to this article.

-

Note that the court answered four certified questions this year, which we excluded to be consistent with the previous study’s methodology. ↑

-

Justice Kruger wrote a concurring opinion in People v. Lewis (2023) 14 Cal.5th 876, which Justice Groban joined. ↑

-

People v. Braden (2023) 14 Cal.5th 791. The majority held defendants are not eligible for post-conviction mental health diversion; Justice Evans authored a dissent and Justice Liu joined. ↑

-

People v. Brown (2023) 14 Cal.5th 530. The majority held a trial court abused its discretion in denying the People’s request for a continuance; Justice Groban authored a concurring/dissenting opinion and justices Liu and Evans joined. ↑

-

People v. Schuller (2023) 15 Cal.5th 237. The court found instructional error and reversed a murder conviction; Justice Liu authored a concurrence arguing for reconsidering the standard for imperfect self-defense, and Justice Evans joined. ↑

-

People v. Mumin (2023) 15 Cal.5th 176. The court reversed an attempted murder conviction based on instructional error; Justice Liu authored a concurrence arguging against using the “kill zone” theory and Justice Evans joined. ↑

-

Goodwin Liu, How the California Supreme Court Actually Works: A Reply to Professor Bussel (2014) 61 UCLA L. Rev. 1246, 1252–54. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Id. at 1256. ↑

-

Bob Egelko, “California Supreme Court consistently unanimous, even in contentious cases,” San Francisco Chronicle September 11, 2020. ↑

-

Victor Eugene Flango, State Supreme Court Opinions as Law Development (2010) 11 J. App. Prac. & Process 105, 118 (emphasis original). ↑

-

There are contrary views. See, e.g., Choi, Gulati & Posner, Which States Have the Best (And Worst) High Courts? (2008) John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper (2d Series) No. 405 (“All else equal, a judge who publishes more opinions is better than a judge who publishes fewer opinions”). Yet if it were true that only the tally matters, a justice could be artificially more “productive” by writing more separate concurring or dissenting opinions, “which would be counter to the primary function of supreme courts to clarify the law and reconcile conflicting interpretations.” Flango, 11 J. App. Prac. & Process at 111. ↑

-

Id. at 106 (“a primary rationale for the creation of intermediate appellate courts is to dispose of the bulk of appeals so that supreme courts can focus on cases with significant policy implications or cases of high salience to the public”). ↑

-

Cal. Rules of Court, Rule 8500(b). This is the first of four listed grounds for granting review; the other three are more procedural than substantive. See also The Supreme Court of California (Seventh Ed., 2019) at 1 (“In deciding which cases merit its review, the Supreme Court focuses on significant legal issues of statewide importance.”) and 2 (“The California Supreme Court may review decisions of the Courts of Appeal to settle important questions of law and ensure that the law is applied uniformly in all six appellate districts.”). ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 5. ↑

-

Kagan, Cartwright, Friedman & Wheeler, The Evolution of State Supreme Courts (1978) 76 Mich. L. Rev. 961. ↑

-

Harry P. Stumpf & John H. Culver (Longman Publishing Group 1992) The Politics of State Courts at 137. ↑

-

Id.; see also Choi, Gulati & Posner, Judicial Evaluations and Information Forcing: Ranking State High Courts and Their Judges (2009) 58 Duke L.J. 1313, 1335 and 1338 (Regarding Georgia’s position as most opinions per year per justice at 58.33, theorizing that “maybe the Georgia judges produce more opinions at the expense of quality” and “perhaps, on further examination, it will turn out that the Georgia opinions are all short, low-quality opinions”). ↑

-

Roy A. Gustafson, Some Observations about California Courts of Appeal (1971) 19 UCLA L. Rev. 167, 177 (yearly maximum of 210 working days for California Supreme Court justices). ↑

-

Flango, 11 J. App. Prac. & Process at 113. ↑

-

Carrington, Meador & Rosenberg, Justice on Appeal (West 1976) 145–46. ↑

-

Leflar, Delay in Appellate Courts, in John A. Martin & Elizabeth A. Prescott, Appellate Court Delay (NCSC 1981) at 151. ↑

-

Flango, 11 J. App. Prac. & Process at 113 (examining signed opinions issued by state high courts for the 20-year period from 1987 to 2006) and 116 (distinguishing results by number of justices). ↑

-

Choi, Gulati & Posner, Judicial Evaluations and Information Forcing: Ranking State High Courts and Their Judges (2009) 58 Duke L.J. 1313, 1335 (the study period was 1998 to 2000). ↑

-

William Wirt Blume, California Courts in Historical Perspective (1970) 22 Hastings L. J. 121, 179–80. Note that retained justices behave more like appointed justices than elected justices. See, e.g., Canes-Wrone, Clark & Kelly, Judicial selection and death penalty decisions (2014) American Political Science Review, 108, 23–39. ↑

-

Chronicle Editorial Board, “Judicial elections are the most confusing items on California’s ballot. Why do we have them?“ San Francisco Chronicle December 23, 2023 (In 2000, state legislators tried to shift Superior Courts to a retention system, in which judges can removed by vote, but the governor would choose their replacement. That effort failed.). ↑

-

There are also conceptual problems inherent in studies that attempt to assign measurable values to appellate judicial opinions. Hall & Wright, Systematic content analysis of judicial opinions (2008) 96 Cal. L. Rev. 63, 82 (“the precise methods used to quantify cases are subject to a number of criticisms”). Even more suspect are studies that attempt to gauge how much an opinion influences action by other government branches. See, e.g., Corley, Howard, & Nixon, The supreme court and opinion content: The use of the federalist papers (2005) Political Research Quarterly 58, 329–340; Owens, Wedeking, & Wohlfarth, How the supreme court alters opinion language to evade congressional review (2013) Journal of Law and Courts 1, 35–59; Posner, An economic analysis of the use of citations in the law (2000) American Law and Economics Review 2, 381–406. ↑

-

See, e.g., Friedman, Kagan, Cartwright & Wheeler, State Supreme Courts: A Century of Style and Citation (1981) 33 Stan. L. Rev. 733; Mott, Judicial Influence (1936) 30 Amer. Pol. Sci. Rev. 295. ↑

-

Choi, Gulati, & Posner, Professionals or politicians: The uncertain empirical case for an elected rather than appointed judiciary (2010) Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 26, 290–336 (appointed justices are less likely to use opinions as tools to connect with external actors, and instead are likely will focus on longer-term policy goals and creating precedent). ↑

-

Jake Dear & Edward W. Jessen, “Followed Rates” and Leading State Cases, 1940–2005 (2007) 41 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 683, 683. See also Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & Eric A. Posner, Judicial Evaluations and Information Forcing: Ranking State High Courts and Their Judges (2009) 58 Duke L. J. 1313, 1337 (“California is far ahead of the other states in both total number of citations and citations per judge-year.”). ↑

-

Choi, Gulati & Posner, Judicial Evaluations and Information Forcing: Ranking State High Courts and Their Judges (2009) 58 Duke L.J. 1313, 1337. ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 7. ↑

-

Black & Spriggs, An Empirical Analysis of the Length of U.S. Supreme Court Opinions (2008) 45 Hous. L. Rev. 621, 663 (minimum-winning decisions are significantly longer). This study used the an opinion’s length as proxy for the “legal style, culture, quality, complexity and even the extent to which the law within an issue area has settled.” Id. at 626. ↑

-

Owens, R. J., & Wedeking, J. P. (2011). Justices and legal clarity: Analyzing the complexity

of U.S. Supreme Court opinions. Law & Society Review, 45, 1027–61. ↑

-

Canon & Jaros, External Variables, Institutional Structure & Dissent on State Supreme Courts (1970) Polity 3(2): 175–200. ↑

-

Brace & Hall, Neo-institutionalism and Dissent in State Supreme Courts (1990) The Journal of Politics 52(1): 54–70. ↑

-

See, e.g., Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) 163 U.S. 537, 554–55 (“I deny that any legislative body or judicial tribunal may have regard to the race of citizens when the civil rights of those citizens are involved”) (Harlan, J., dissenting). ↑

-

Id. at 727. ↑

-

Choi, S. J., Gulati, G. M., & Posner, E. A., Professionals or politicians: The uncertain empirical case for an elected rather than appointed judiciary (2010) Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 26, 290–336. ↑

-

For a contrary view, see Leonard & Ross, Understanding the Length of State Supreme Court Opinions, American Politics Research 2016, Vol. 44(4) 710, 725 (finding there “is simply no evidence of a direct relationship between the method of selection and the length of the majority opinion”). ↑

-

Choi, Gulati & Posner, Judicial Evaluations and Information Forcing: Ranking State High Courts and Their Judges (2009) 58 Duke L.J. 1313, 1349. ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 3. ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Understanding the Length of State Supreme Court Opinions, American Politics Research 2016, Vol. 44(4) 710, 714. ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 9. ↑

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 11 (a smaller workload facilitates the selection of interesting or important cases likely to garner more attention and provides more time for writing separate opinions). ↑

-

Consensus is also the norm on the U.S. Courts of Appeals, with an overwhelming majority of their cases decided unanimously, partly due to lack of resources to write separate opinions. Hettinger, Lindquist, & Martinek, Judging on a Collegial Court: Influences on Federal Appellate Decision Making (University of Virginia Press 2006) at 19–20. And for what it’s worth (and we often resist this comparison) a norm of consensus also prevailed at the U.S. Supreme Court “for much of its history,” a “norm of unanimity that lasted well into the twentieth century.” Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 3–4 and 5. ↑

-

Leonard, M. E., & Ross, J. V. (2013, January). Disagreement in state supreme courts. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, Orlando, FL. ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 17 (“the methods of selection and retention have a significant and consistent influence on the opinion-writing process” and “the likelihood of a unanimous decision is higher on appointed courts than elected courts”). ↑

-

Cf. P.J. O’Brien, Will Rogers: Ambassador of Goodwill, Prince of Wit and Wisdom (John C. Winston, Philadelphia, 1935) at 162 (“I’m not a member of any organized party — I am a Democrat.”). ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 7–8 (“Compared with a court where justices face only retention elections or no elections whatsoever, elected courts in general should be characterized by lower levels of cooperation among justices in their day-to-day work.”). ↑

-

Leonard & Ross, Consensus and cooperation on State Supreme Courts (March 2014) State Politics & Policy Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 1, at 19. ↑

-

The Commission on Judicial Appointments confirmed Chief Justice Guerrero’s appointment as chief justice on August 26, 2022. Justices are confirmed by the Commission on Judicial Appointments only until the next gubernatorial election, at which time they run for retention of the remainder of the term, if any, of their predecessor, which will be either four or eight years. Cal. Const., art. VI, section 16(a), (d)(1) and (d)(2); Elections Code section 9083. ↑